|

| Based

on booklet entitled:

The

Story of the Powder River Let'er Buck, |

| CusterMen MENU: | Italian Campaign | At The Front | Books | Armies | Maps | 85th Division | GI Biographies | Websites |

|

| Based

on booklet entitled:

The

Story of the Powder River Let'er Buck, |

|

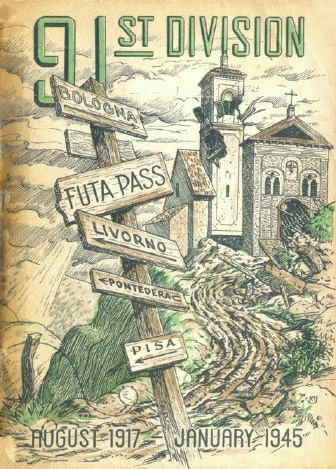

The

"91st Division" history was a 94-page

booklet published by the 91st Division during the last months of the

war

for distribution to the soldiers and their families. This booklet gives

a good overview of the history of the 91st Division with details about

places and events. The booklet contained photos and sketched

maps,

which are not included. The history of the 91st is quite different than the ones for the 85th Division and the 1st Armored Division. The History of the 91st seems to be bragging a lot about being "first" to reach certain objectives. Some of these "firsts" occurred because they were the ones assigned this objective and not because their performance was better than other units. Also, the 91st Division arrived later than many of the other divisions, which meant it was a fresh unit and it was only in combat for 4 months when the book ends. The booklet ends with the capture of Livergnano at the Gothic Line defense in October 1944. The remainder of the combat history was omitted so the booklet could be published. The 91st Division would continue service in Italy as part of the 5th Army. It performed outstanding service during the Po Valley Campaign in April 1945, which saw the collapse of the German resistance in Italy. Steve Cole |

| TABLE

OF CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION - (Not Included) CHAPTER I - 91st Division in World War I CHAPTER II - THE FIRST TWO YEARS: 15 AUGUST 1942- 12 JULY 1944 CHAPTER III - ARNO RIVER CAMPAIGN CHAPTER IV - THE GOTHIC LINE CAMPAIGN CHAPTER V - NORTH OF FUTA PASS

Allied Units (Only highlight units other than the 91st Division) German Units Bold (black) Important dates, towns or leaders. {My comments} in Blue Brackets. S. - San or Saint. S. Pietro for San Pietro. TOT's - Time of Target. A firing command for artillery. 130400 - Date/Time identifier for 13th day of month & 0400 hours. 191500 is 3:00pm on 19th. The 91st Division was part of the 5th Army. The divisions within the 5th Army were orgnaized into Corps. During various times, the 5th Army consisted of the II Corps, IV Corps and/or VI Corps. Note, the text mentions III Corps but this was prior to deployment to Italy. During WW2, the typical Infantry Division was formed as a “triangular unit”, which meant the division consisted of 3 Regiments. The 91st Division contained the 361st, 362nd & 363rd Regiments. Each Regiment consisted of three battalions that commanded four companies. The 1st Battalion consisted of Companies A, B, C, & D; the 2nd Battalion of Companies E, F, G, & H; and the 3rd Battalion of Companies I, K, L, & M(heavy weapons). The Cannon Company was a light artillery unit that reported to the regiment. |

Chapter I

91ST DIVISION IN WORLD WAR I Five months after the United States declared war on Germany in 1917, the original 91st Infantry Division was activated at Camp Lewis, Washington. Most of the men came from the states of the Northwest, a fact which explains many of the distinctively western traditions and emblems which are part of the heritage of the 91st Division of World War II. Activated under the command of Major General H. A. Greene, the Division immediately plunged into training. The first contingent, which arrived 5 September 1917, was so eager to begin that they drilled in their civilian clothes. After 10 months of training the Division made ready to go overseas. Examined and re-outfitted at the staging area, Camp Merritt, New Jersey, the first elements sailed for France 6 July 1918. Most of the men landed in England, although a few were taken directly to France. By 1 August the Infantry Brigades had been gathered at Montigny le Roi, and the Artillery Brigade at Camp de Souge and Clermont-Ferrand. At these places the men underwent a month of incessant drilling and long hours of marching, until they were declared ready for actual combat. On 29 August Major General William Jonhston assumed command of the Division, and a very few days later, 7 September, it was assigned to reserve of the First American Army during the St. Mihiel offensive, with headquarters at Sorcy. Combat

and steadfastly clung to every yard gained. In its initial performance, your Division has established itself firmly in the list of the Commander-in-Chief’s reliable units. Please extend to your officers and men my appreciation of their splendid behavior and my hearty congratulations on the brilliant record they have made..”

One of the great honors given the Division came on 16 October {1918}, when, along with the 37th Division, it was named as part of the armies in Flanders, which, under King Albert, were about to launch the final crushing drive t the enemy in Belgium. The 91st attacked in the early morning mists of 31 October. From that time on until the very moment of surrender, 11 AM on 11 November, the Division drove the enemy back in panic. Although the enemy had been ordered to hold the heights between the Lys and the Excaut Rivers to the death, the 91st smashed them the first day, and by the evening of 1 November they were on the outskirts of Audenande. The next day the town was secured, and the Division pushed on to capture Welden, Petegem, and Kasteelwijk in rapid succession. On the morning of 10 November, with the 182nd Infantry Brigade in the lead, the Division crossed the Scheldt River near Eyne. They drove forward through town after town, and had advanced beyond Moldergem when the order came to cease firing. In recognition of the superb courage and fighting ability, the 91st Division had shown Major General De Goutte, who had resumed command of the Sixth French Army, issued an order which read, in part: Divisions, United States Army, which brings about valiant soldiers and victorious armies. Glory to such troops and to such commanders. They have bravely contributed to the liberation of a part of Belgian territory ad to final victory. The great nation to which they belong can be proud of them.” |

Chapter

II

THE FIRST TWO YEARS: 15 AUGUST 1942 - 12 JULY 1944 “March,

Shoot, and Obey”

Early in September occurred the famous 91-mile march, of which the original members of the Division still reminisce. Undertaken to instruct the cadre in marches and bivouacs and to test the best physical powers of the officers and men, the march of 91 miles was made through the rough roads and trails of the Cascade Mountains. The distance was covered in 28-3/4 hours of actual marching time. With the grueling test passed, the cadre settled down to the training of the men sent to the Division. During October and November, over 12,000 men poured into Camp White from all parts of the country and the training of these men began in earnest. Nearly all of them had no previous military training and so, on 15 November, they began with the basic fundamentals. The training period covered 39 weeks; basic training lasted until 15 February: unit training in platoon and company formations occupied the next 13 weeks, 15 February to 13 May. The last 13 weeks, devoted to the tactics of the Battalion and Regiment, were climaxed by maneuvers involving the whole Division held in the vicinity of Camp White, 21 June – 10 July 1943. Maneuvers

In all, there were eight problems in which the 91st, together with the 96th and the 104th Divisions, took part in both offensive and defensive operations over desert and mountain terrain. The extremes of heat and cold, the excessive dust, snows and rain, and the difficult terrain tested the endurance, and ingenuity of every officer and man. The exercises accomplished their purposes and the three Divisions, which had participated, emerged hard, well-trained fighting units ready to take their places in theaters of combat. From Bend the Division moved to Camp Adair, near Albany, Oregon, 2 November 1943. The lessons learned in the maneuvers were thoroughly studied and every effort was made to polish the rough edges wherever they had appeared in anticipation of an early alert for movement overseas. It was not a long wait, for the alert came on 20 January 1944. “P.O.M.”

The message from Major General John Millikin, III Corps, directed the Division to conduct immediate inspections, intensify training, complete firing, and expedite shortage lists at once and to submit a personnel status report on or before 28 January 1944. It further charged the Division with submitting a training status report on 5 February 1944, showing the exact status of training. Schools on boxing and crating, servicing of vehicles and weapons for overseas shipment, Personal Affairs, and Malaria Control were immediately conducted for all personnel of the Division. On 28 January 1944 the War Department published the formal movement orders setting the readiness date as 1 March for personnel and accompanying equipment, and 15 February for the Advance Detachment. During the following weeks the great pattern of preparation for combat was woven into a fabric that was strong and enduring-that would withstand the test of battle without revealing miscalculations that foresight and planning could prevent. The Division cleared its personnel ineligibile for overseas service and received the necessary replacements: it requisitioned equipment and. issued it to the units concerned, furloughs were granted to those eligible, security was maintained, the physical fibre of the men was tested - corrected when possible - by the Division Surgeon. Training was pushed to completion and immunizations were given. Gradually the ideal of complete preparedness grew in to fact, and on 8 March General Livesay was able to report to III Corps that all arrangements short of the last minute details had been completed and that the Division was ready to move. The preparation of the Division had been completed in exactly 48 days. Four days after the General had reported the Division ready the War Department set the final readiness dates: 20 March for personnel and accompanying equipment, 12 March for the Advance Detachment, and 14 March for the impedimenta. It would be a mistake to imply that during this brief time of preparation the Division had made no mistakes in its gigantic task. As a whole, however, the work had been completed smoothly, without confusion or strain. When on 11 March the first call from the port was received, General Livesay immediately called a conference of his staff and unit commanders and carefully outlined the final plans, answered questions raised and quietly ended: the problems we are going to face during the next year; so let us start off in the right manner, with the Advance Detachment getting off tomorrow and the impedimenta on the 14th and the rest of the Division on time."

Staging

General Livesay, accompanied by Colonel Donnovin, Chief of Staff, and Captain Lash, Aide-de-Camp, proceeded by air after the departure of the first increment. They departed from Washington 5 April, and after conferences in Algiers, flew to Naples for instructions, arriving 10 April. They flew back to Algiers 16 April, and then to Oran to await arrival of the Division. The second echelon left the Port of Embarkation 3 April. At sea its destination was suddenly changed from Naples to Oran, the Allied Base in Algeria. This did not vitally affect the movement, but it did become immediately necessary for the Advance Detachment, already at Naples, to return to Africa and reestablish the 91st Division's forward headquarters. Thus, shortly after midnight on 14 April, this group left Italy by plane and organized the forward Command Post of the Division at No. 10 Rue Gallieni, Oran. The first increment of Division arrived in convoy off the shores of Mers-el-Kebir 18 April, debarked and moved to permanent bivouac areas, with headquarters in Port aux Poules. Back in the United States the third echelon--aware of the Division's new destination--sailed 12 April and arrived at Mers-el-Kebir on the 30th. The 2nd Battalion of the 363rd Infantry left Hampton Roads on 21 April and arrived in North Africa 19 days later, on 10 May. This officially closed the Division in North Africa, and General Livesay wired the Commanding General of the North African Theater of Operations: "last elements of the 91st Division closed in Theater 10 May 1944, End." Thus the Division which had been alerted on the 20th of January and whose first contingent did not leave the West Coast until 14th of March, accomplished the approximately 7,500-mile operation in exactly 54 days. Training

in Africa

The whole program was divided into two basic phases: individual and small unit training and then Battalion and, in one case, Regimental landings. There was training in the organization of boat teams, wire breaching, debarkation drill, demolition teams, rocket teams, flame throwers, and a dozen other aspects of invasion technique. Then during the final period, units made landings on beaches in Arzew Bay in battalion strength both at night and during the day. During these landings, it was the mission of the troops to push through a heavily fortified zone, with barbed wire entanglements, pillboxes, and tanks; to climb mountainous terrain, to land artillery from the sea, and to fight under the guns of naval support. It was the toughest single period of training that the Division had undergone. The 361st Combat Team, commanded by Col. Rudolph W Broedlow, completed its course on 15 May and left the Division on detached service with the Fifth Army in Italy. The 362nd Combat Team began its schedule on 11 May. The training was the same as that of the 361st with the exception that it executed a regimental landing, whereas the 361st had operated only in battalion strength. Its training ended on 19 May, shortly before the 363rd Combat Team began, and by the end of May all, the combat teams had completed the entire course. "Dry

Run"

for Combat

D-Day

for

the

all-out assault against enemy position on the coast of Arzew Bay was

scheduled

for 11 June. It was assumed that the area from Oran to Mostaganem was

held

by elements of the German Infantry Division "W" with the "Y" Grenadier

Regiment at Oran, the "X" Grenadiers at St. Cloud, and one Battalion of

the "Z" Grenadier Regiment at Mostaganem. The entire stretch of the

beach

was strongly fortified with pillboxes, barbed wire entanglements,

anti-tank

traps, and strong points. There was also a force of enemy tanks

reported

in the vicinity prepared to repel any possible attack. The Division's

mission

was to seize the Port of Arzew and the airport at the town of Renan.

Its

final objective was the high ground west of Renan and south of Kleber.

The plan called for a coordinated attack by both the 362nd and 363rd

Regimental

Combat Teams with engineer, medical, AAA, air and naval units in direct

support.

Endless landing ships of all types were massed for the "Invasion." The Division CP was established on the USS Biscayne while an alternate CP was established on the HMS Derbyshire. Troops began embarking on 9 June. The following day was spent in briefing the commanders and men on the specific plans of the mission. Then, late that same night, 10 June, the ships moved slowly out of the harbor of Oran under cover of darkness and steamed silently ten miles out to sea opposite Cape Carbon and the shores southeast of Arzew. During the night the troops were loaded into small landing craft, while a heavy sea rolled against the sides of the ships. Forty-five minutes before H-Hour, 0400, navy destroyers laid down a heavy artillery barrage on the beaches. Under this protective covering the first assault teams moved toward the hostile shore. The 363rd, getting off to a late start because its landing was forced off course by the wind, attacked at 0440 on the narrow "Ranger" beach just south of Cape Carbon. They landed in 14 waves and when they hit the beach they struck hard. Within 12 minutes the first wave had breached the initial wire entanglements at the beach's edge and was moving south to its next phase line. By the end of the first hour the Regiment had knocked out the enemy pillboxes with flame-throwers and demolition charges. Meanwhile, at 0510, the 362nd Combat Team moved against the enemy's defenses on the Arzew shore, cut the road leading to the city and struck 1000 yards inland to its first objective. By 1000 the entire Regiment was ashore and the town had been captured. Reverting to the approach march formation with the 3rd Battalion in the lead, the Regiment advanced on the Division objective and by 1400 had joined forces with the 363rd on its right flank in seizing the high ground south of Kleber. The operation, viewed as a whole, was declared a success, and the training went a long way toward hardening the Division for the combat it was to meet in the Italian front. {End of amphibious training.} Italy

Baptism

of Fire

One of the stiffest engagements was met at Ponte d’Istia on the Ombrone River. Here the Germans had a strong holding position in the town and two hills nearby. By infiltrating a whole Battalion over a partially destroyed dam single file, one man at a time, and by taking advantage of all avenues of covered approach, the Regiment completely surprised the enemy. Although they made a determined effort to stop the attack with heavy artillery and mortar concentrations, the 3rd Battalion pushed ahead, and by 162030 June they had captured Hills 61 and 66, as well as the town of Ponte d'Istia itself. Many casualties were inflicted on the enemy in the engagement and approximately 80 prisoners were taken. The rapid advance northward continued until 19 June, when the Regiment was assembled near Batignano. Here, after a day's rest, they were attached to the 1st Armored Division. To all intents and purposes the Regimental Combat Team for the time being lost identity. The 2nd Battalion was attached to Task Force Howze, while elements of the other Battalions were attached to any one of three motorized Combat Teams as supporting infantry. The mission of the infantry was to ride the tanks and the tank destroyer decks until opposition was encountered: then the infantry was to deploy and attack. The main axis of advance was the Batignano-Paganico-Roccostrada Highway. During the following two weeks the men of the 361st Infantry saw much action. The most bitter engagement of the period occurred at Casole d'Isola, where the fighting lasted for four days, 1-4 July. After the town had been captured, elements of the Regiment were relieved. On 6 July elements of the 2nd and 3rd Battalions returned to the control of the 361st Infantry and the Regimental Combat Team returned to the control of the Division. On 4 July the 363rd Regimental Combat Team commanded by Col. W. Fulton Magill, Jr. was attached to the 34th Division to gain combat experience and entered combat near Riparabella. Attacking through mountainous terrain they captured M. Vaso on 6 July and held it against very strong counterattacks. Although they were forced by their losses to withdraw briefly, the hill was secured on 9 July, and the advance continued toward the high ground west of Chianni. Opposition was light but progress was slow, mainly as a result of the very difficult supply situation. |

|

North to

the Arno

Fifth

Army

began massing its forces during the first weeks of July. The veteran 34th

Division, with many attached units was

hammering at the outer defenses of Leghorn, while the 88th

Division on the right flank was

striking

for the high ground south of the Arno to outflank it. The 91st Infantry

Division was assigned the central sector between the 34th

Division and the 88th

Division.

At 0300 on 12 July 1944 the 91st Division entered combat for the first time as a complete unit. Its objective, the high ground dominating the Arno River, lay 15 miles away. Heavy opposition was expected because the enemy had all the advantage of prepared positions in mountainous country that was ideal for defense and because the enemy was known to be massing a small force of tanks and mining every approach. On the left, the 363rd Regimental Combat Team, which had been fighting for 9 days with the 34th Divisions came under Division control and attacked .on a four mile front south of Chianni. On the right, General Livesay deployed the 362nd Infantry, the only Regiment which had had no combat experience prior to the commitment of the Division north of the Cateste Hills with the Sterza River and the Casaglia-Capannoli Highway as its axis of advance. First

Phase

Progress during the Division’s first day of combat was most gratifying. On the left, the 363rd Infantry, advancing in a flanking movement west of Chianni, took Hills 553 and 577, dominating the approaches to Chianni, and Hill 477, a mile northwest of the town. Although the 3rd Battalion was ordered to enter Chianni itself, Italian Patriots reported that the enemy had retreated and that the Patriots were mopping up. Thus only patrols were sent, while the main force proceeded northward along the ridge wet of Rivalta. On the right, the 363nd Infantry met stiff opposition protecting the Chianni-Laiatico road. At Pgio Le Grotte, on the Division Line of Departure, the Regiment met its first real baptism of fire. This opposition was overcome by dawn, but the enemy fell back slowly. The 2nd Battalion attacking along the left flank of the Regimental sector, was met by a force of 12 enemy tanks. Artillery fire was placed on them, knocking out one and forcing the rest to disperse. In two attacks late in the day, at 1640 and at 2010, the Battalion drove to within a half mile of Chianni. The 3rd Battalion found the enemy determined to hold the Chianni-Laiatico road, and although it smashed 500 yards beyond the road during the day a very heavy counterattack forced it to withdraw. Second

Phase

The drive of the 362nd Infantry was slowed somewhat by the heavy artillery fire from Terriciola to the north and by SP fire from the vicinity of Chianni. Although the Division Artillery knocked out one of the self-propelled guns and silenced the rest early the second day, the fire again harassed the Regiment in the afternoon. This time the Cannon Company knocked out one of the guns and forced the other two to withdraw. With the harassing artillery and SP fire neutralized, the Regiment moved forward slowly and had secured Terriciola at last light 14 July. Meanwhile the 363rd Infantry after consolidating its gains of the first day, reached a point just south of Bagni. Patrols were sent out to both the left and right; one of the latter was so zealous as to reach Terriciola, where it assisted in the capture of the town by the 362nd. At 0400 15 July the 361st Infantry, having passed through the 363rd Infantry at Bagni, attacked north. Meeting no resistance, they pushed rapidly through Morrona. After the infantrymen had occupied ground north of Soiana, however, they were subjected to a steady pounding of well-observed enemy fire. Likewise in its advance north from Casanova the 362nd Infantry was subjected to heavy artillery, mortar, and machine gun fire from Selvatelle. After an extended preparation Selvatelle was by-passed. But the advance was slow because of the continuing heavy enemy fire, and at the end of the day the Regiment was pinned down north of the Arno. Third

Phase

The next morning the 3rd Battalion, 361st Infantry, supported by two companies of tanks jumped off again. In addition to the customary artillery and automatic weapons fire, the enemy employed armor to halt the advance. It was estimated that 25 enemy tanks, Mark II's IV's and VI's; were operating in the zone of the 361st. All morning there was a constant threat of an armored counterattack developing at Orceto. Stopped once by Cannon Company fire, it developed again, only to be stopped once and for all when the 698th Field Artillery fired 25 rounds of 240mm into the town and its vicinity. The main push continued, and by noon Companies I and K, had reached Ponsacco. The town was enveloped and shelled by tank fire; after this preparation the infantry occupied the town with little resistance. First at

the Arno

Coincident with the brilliant drive of the 361st Infantry up the Ponsacco-Pontedera road, the 362nd Infantry on the right flank moved steadily forward in its sector. On 15 July General Livesay visited the Regimental CP and expressed his pleasure at the successes scored by the 362nd. This was a tonic to the weary, hard-fighting men, and at 160800 they moved out to the attack with new vigor. Fighting steadily throughout the day and the following night, they were well on the Divisional objective, the high ground south of the Arno, at 0800 17 July. At this stage the enemy loosed a terrific barrage of 88mm artillery and mortar fire, so heavy that the entire Regiment was checked. Although the 346th FA attempted to silence the opposition, limited observation prevented successful accomplishment of the mission. As a result, the front lines withdrew slightly to positions better situated to repel a possible counterattack. The attack was resumed at 180330, with the 3rd Battalion, 362rd Infantry, replacing the 1st in the front lines. The advance was slow-not because of enemy resistance, which was slight, but because of the terrain, which was very rugged. During the morning the troops were delayed by artillery fire from the area of Treggiaia north to the river, and by Shu mines, the first the Regiment had encountered. About noon, the Germans were observed pulling their artillery back across the river. On the next day at 0800 the advance was again taken up, this time without enemy resistance. Terrain, demolitions, and mine fields slowed the advance but at 191500 the Regiment had closed on its objective. One company from each Battalion outposted the line, and patrols were sent to the Arno River. "Well

Done,

91st Division"

of determination and pride of service in all ranks that assures the further success of the Division.”

First in

Leghorn

The 1st Battalion and the 2nd Platoon of the 91st Reconnaissance Troop striking from the high ground east of the port were the first to enter Leghorn that night. The 2nd and 3rd Battalion moved in the following morning and reorganized for the attack on Pisa. Enemy resistance by this time was completely shattered, and the main forces were withdrawing towards Pisa. First at

Pisa

From 23 July until 28 July, when it was relieved, Task Force Williamson was under constant artillery, mortar and small arms fire from German lines across the river. At first enemy patrols came across in small boats to reconnoiter the American positions. But General Williamson thwarted the moves by establishing strong points at strategic positions. On the night of 28 July the 363rd was relieved and withdrew south of Leghorn in preparation for movement to the east, where it was assigned the mission of screening Fifth Army's right flank and maintaining contact with the 88th Division. Commendations

of the men of the 91st Division. The valiant deeds of these men and their outstanding contribution in this Italian campaign will go down in history as another great military achievement of American arms.”

"Patrols

Were Active"

The 362nd Infantry, occupying the positions along the river had two primary missions; to learn as much as possible about the enemy's strength, position, fire-power, and movement, and to scout the river and its banks for information to be used in a possible river-crossing operation later in the month. Its second mission was to screen the front of the Division and Fifth Army and deny the enemy knowledge of the disposition and movements of our troops. To complete these missions an average of five combat patrols consisting of from eight to twenty men, and fourteen reconnaissance patrols of four to eight men, with an officer leading each patrol, covered prearranged routes each night. In addition to the combat and reconnaissance patrols sent out by the infantry the 316th Engineer Battalion sent out reconnaissance parties to gather information essential to crossing the Arno. One such party reconnoitered the terrain for three nights and two days, 18-22 August 1944. They waded and swam the river at many times and places to determine depths and widths of the stream and gathered other information concerning the banks and approaches. From prisoners captured by combat patrols and from the reports of the reconnaissance parties of both the Engineers and the 362nd Infantry, the Division gradually built up a complete and accurate study of the disposition of enemy forces as well as a detailed analysis of the Arno River and its banks. While the 362nd Infantry was patrolling the Arno, 1-13 August, the other two Regiments and Division Artillery concerned themselves with the care and cleaning of equipment, training, and study. On 5 August training was instituted in the 361st Infantry stressing marksmanship and physical conditioning designed to bring the 1,000 replacements which had come to the Regiment since 3 June up to Regimental standards. Instruction in scouting and patrolling, mines and mine warfare, and technical training for special units was also carried out. In the 363rd Infantry, essentially the same program of training was undertaken for those not actively engaged in the Regimental mission of screening the Division's right flank and maintaining contact with the Eighth Indian Division. In addition, every replacement had an opportunity to gain actual patrol experience under the leadership of experienced leaders. Division Artillery, in addition to activities similar to those of the Regiments, concentrated on the care and cleaning of their equipment. The armament section of the 791st Ordnance Company, with the help of 12 men from the automotive section, performed the six month's survey of the Division's artillery pieces. Visitors

Five days later Mr. Robert Patterson visited the Division. With his party he visited the Command Post of the 361st Infantry and presented decorations to six Officers and Enlisted Men and personally greeted a Guard of Honor of fifteen men who had previously been decorated by the Division for heroism. After reviewing the 2nd Battalion of the 361st and addressing the troops briefly, he was taken to the Division Command Post, where he and his party were the guests of General Livesay at luncheon. Second

Anniversary

the enemy under the most trying circumstances of terrain and has driven him back with heavy casualties. I feel certain that the German high command has this Division registered as one of the first line fighting divisions. The campaign to the ARNO; the taking of LIVORNO, and the investment of PISA leave no doubt in my mind but that I have the honor to command an organization of top-class fighting men. With all of my pride in you, I am still inclined to sound a note of warning. Let us steel ourselves to further, more definite efforts. Let us improve ourselves in all of the things that we have learned so that nothing can stand successfully in the path of the Division."

|

|

“. . a lifetime of .. . fear, courage and prayers.” DURING

THE MONTH of September the 91st·Division fought its most

brilliant campaign, in which it smashed the most formidable defensive

positions

in Italy, the Gothic Line. It advanced through elaborately constructed

fortifications over mountainous terrain made hazardous by rain and fog,

with unflinching determination and unwearying courage. According to one

infantryman the climactic days, 12-22 September, were a "lifetime of

mud,

rain, sweat, strain, fear, courage, and prayers." But with brilliant

leadership

and magnificent courage, the 91st Division cracked the Gothic Line and

established itself as one of the great fighting Divisions of World War

II.

Contrary to expectation the German high command did not elect to make a stand at the Arno but withdrew to their prepared positions north of the Sieve River. According to Intelligence reports the Division was facing four Divisions, estimated to number 12,600 men, with at least one Division of 2100 men held in reserve in the vicinity of Prato. The first extended stand was anticipated at a line running from Fontebuona, through Ferraglia, Bivigliano, and M. Senario to Il Poggiolo. The Division moved across the Arno with the utmost secrecy on 6 September, and assembled on the north bank, screened by the British Eighth Indian Division. While the British were screening the Division's movements, however, they found that the enemy had begun to withdraw. The Eighth Indian Division under the operational control of the 91st Division, sent out patrols constantly in an effort to maintain contact with the withdrawing enemy. On 8 September, when patrols reached Farraglia, Bivigliano, M. Senario, and M. Calvana and found the positions unoccupied, the British units moved forward to occupy the line. Moving Up

Jump Off

The next morning, 11 September, the two Regiments continued the attack. Since the Germans had withdrawn from their outpost line upon contact, there was little resistance. Only the mountainous terrain and enemy minefields slowed the advance. At the end of the day the 362nd Infantry was just north of Gagliano, while the 363rd Infantry had occupied San Agata. The next morning the attack continued against steadily increasing resistance. The 363rd Infantry advancing toward Monticelli, and the 362nd moving on M. Calvi met small arms and mortar fire as well as harassing artillery fire. The main obstacle, however, was the mountainous terrain which grew steadily more difficult as the troops advanced toward the ridge line of the Apennines. In the afternoon, 13 September, General Livesay ordered the 361st Infantry committed. The Regiment was to pass through forward elements of the 363rd Infantry on the left and to attack at 140600 in the center of the Division sector. On the right, the 363rd was ordered to secure Monticelli; on the left the 362nd was ordered to secure M. Calvi and then proceed to its next objectives, M. Poggio all Ombrellino and M. Gazzaro. Thus until the 363rd reverted to reserve, the 91st Division was to have nine Battalions on line: three on the left, one moving north near Highway 65, and two attacking M. Calvi; three in the center attacking Hills 844 and 856; and three on the right attacking Monticelli. The great drive on the main defenses of the Gothic Line was now begun. Unlocking

the Door: Monticelli

As further protection row after row of barbed wire, one foot high and 25 feet deep, had been placed at 100-yard intervals up to the top of the mountain. In two ravines, which led to the top of the mountain, the enemy had laid minefields. On the reverse slope of Monticelli elaborate dugouts had been constructed. These had been dug straight back into the mountain to a distance of seventy-five feet and were large enough to accommodate twenty men. On a hill 300 yards north of Monticelli a huge dugout was found which had been blasted out of solid rock. Shaped like a U and equipped with cooking and sleeping quarters, it was large enough to accommodate 50 men. The

Advance

Was Slow.. .

After two days of slow progress the first break in the enemy defenses developed. Company B over-ran the enemy Main Line of Resistance and occupied the ridge line extending west from the peak of Monticelli. Although the Company was subjected to counterattack after counterattack and unrelenting artillery and mortar concentrations, the flank was never turned. After one Counterattack two enemy were found sleeping in Company B foxholes! The

Final

Assault

"The

Situation

Is Well In Hand"

Monticelli had been won by the courage and sacrifice of the 363rd Infantry and the superb support of the 347th Field Artillery and its associated units. The artillery pounded constantly at enemy positions. In one area where artillery fire had been directed for four days, 150 dead were later counted. One of the targets fired during the all-night barrage, 17-18 September, proved to be a Battalion Command Post 30 feet wide dug 100 yards into the side of the mountain. The next day 33 prisoners were taken from the cave, dazed and shaken by the pounding they had received. The artillery had run the enemy into their holes, and the infantry had dug them out, and Monticelli fell. General Keyes, Commanding General, II Corps, expressed his pride in the capture of the key position, the first break in the Gothic Line in the II Corps sector, when he telegraphed to General Livesay: tough assignment is fitting tribute to the dogged determination and courage of the 91st.”

The

Unnamed

Hills

There was a second difficulty which hampered, to a certain extent, all the Regiments of the Division but especially the 361st Infantry. This was the problem of supply. On the left and right, roads were available at least part of the way for the transportation of supplies, but in the 361st Infantry sector the only road of any size running north from San Agata stops at Casal. By ceaseless effort the Engineers rapidly extended a trail to Coppo adequate for quarter ton trucks which ran from Casal to Vallappero. This was unquestionably one of the most difficult assignments the Engineers completed during the month. The trail was so rocky that it was impossible to scrape the road out of the mountainside and so steep on the outside that it was equally impossible to bank it up to a passable width. Yet by blasting and chipping the rock wall and base, Company A, using all three of its platoons in succession working night and day succeeded in widening the trail into a road passable to peeps. It was dangerous, especially in the dark when the drivers could not even see the tracing tape and had to be led along the road by a convoy officer, but it was usable up to Coppo. From Coppo there were only mule trains. For days every drop of medicine and every round of ammunition and every bit of food was carried forward from Coppo on mules. The trail was so narrow and dangerous that it was necessary to set up traffic control points along the way so that the litter bearers bringing out the wounded could pass the mule trains bringing up the supplies. There were, however, excellent reasons for attacking at this point. Within the Division sector it was possible to attack here or at Futa Pass. Futa was the most heavily defended position in the Gothic Line and had the further advantage of being very easily supplied down Highway 65. The section of the Gothic Line in the sector against which the 361st attacked, although very heavily fortified, was not prepared in depth and was very difficult to supply. When the 361st Infantry broke through the Main Line of Resistance in their sector, they found that the enemy failed to solve their supply problem. Most of the prisoners captured had had no food for three or four days and their ammunition supply was very low. Thus, although the sector presented great difficulties for the Regiment in the attack, it presented equal difficulties for defense. The wisdom of the commitment of the Regiment in this sector was borne out by the subsequent success of its drive. “They

Are

Looking Down Our Throats”

The next three days the advance was slowed by barbed wire entanglements, pillboxes, dug in positions, and heavy fire of all sorts. At one point the 3rd Battalion reported that in front of it were “2 banks of wire, each 15-20 feet deep with a space of 20 feet between each, which was undoubtedly heavily mined.” Even 105mm artillery shells could not breach the obstacle. This could only be done by hand, always in the face of terrific fire from well-prepared positions. On one occasion an Engineer was disarming mines while the infantrymen protected him by keeping the pillbox ahead “buttoned up.” As the Engineer, prone on the ground, squirmed from mine to mine, an infantryman called to him to keep his head down. When he protested that his forehead was already touching the ground, the infantryman ordered him to turn his head over to the side so that he could maintain his protective fire! After three days of bitter fighting, pillbox after pillbox had been captured, minefield after minefield had been breached, and barbed wire entanglements had been blown up by artillery shelling and bangalore torpedoes. Savage, bloody counterattacks had been beaten off, and the constant pounding began to tell on the enemy. The same development was observed along the entire Division front. Terrific artillery and mortar concentrations and the constant drive of the infantry had taken their toll. Replacements for the enemy were brought up as early as 13 September, but they were adequate neither in numbers or in combat training. Further, putting these replacements in line was no small task. One prisoner reported that his group had been attacked by American bombers on the way to the line and had suffered heavy casualties. “Many men lost their weapons on the march to the MLR because they were too exhausted to carry them.” The End

in Sight

In the sector of the 361st Infantry this was especially true. By 180650 Companies A and G were reported on Hill 856 and at 180811, Company E reported on Hill 844. The capture of Hill 844 was especially important, for it had been the most strongly fortified and most stubbornly defended hill facing the Regiment. Its loss unhinged the enemy positions in the sector and forced the Germans to retreat. Early in the afternoon as the Regiment pressed forward, the disorganization of the enemy became more and more apparent, as they took hasty positions for a brief stand and then ran back to others. Before the day was over, Hill 805 had been taken. “Objective

Terms”

Futa Pass

Rolling

Barrage

On the same day, 19 September, the 2nd Battalion, attacking from the southeast, captured both Hill 821 and Hill 840. Advancing rapidly to keep contact with the enemy, now driven from his Main Line of Resistance, the Battalion occupied M. Alto during the night of 19-20 September. {Pvt. Oscar Johnson, Company B, 363rd Regiment, earned a Medal of Honor for holding off the enemy attacks for 3 days from his machine gun postion. Five companies of German paratroopers had been repeatedly committed to the attack on Company B without success. Twenty dead Germans were found in front of his position and 25 surrendered.} Although the collapse of the enemy lines in the 362nd sector was not so spectacular as it was in the 361st sector, Hill 896 was captured the next day, and by the morning of 21 September Company A had reached the Santerno and had set up machine guns trained on Futa Pass. In the meantime the 3rd Battalion, 362nd Infantry, which had been operating almost alone, with the closest unit more than 1000 yards away, was battling north along Highway 65. Despite a warning by General Livesay that it was not to try “to win the war by itself” it was trying to do exactly that. On the morning of 16 September the Battalion had come against a spectacular Anti-tank ditch over a mile long over hill and valley and covered by interlocking fields of machine gun fire. Covering the highway was 88mm Tiger tank gun and turret mounted in a concrete emplacement, as well as other concrete pillboxes and dugouts commanding the approaches to the Pass. For two consecutive days the Commanding Officer of the 3rd Battalion, directed the 346th Field Artillery in a steady pounding of San Lucia. The Tiger tank gun was knocked out and two 105mm SP guns were destroyed. Every time the enemy attempted to move, the artillery hit him. On 20 September under a rolling barrage the Battalion attacked along the ridges, surprised the enemy, overran his positions, and captured Hill 689. The next day in a pincer movement they seized San Lucia and, under artillery fire, which was seldom more than 300 yards ahead of the front-line troops, they took Hill 901. That night they outposted in Futa Pass in preparation for the final all-out assault against Hill 952, which commanded the vaunted Futa Pass defense system. The next day, 21 September, the Battalion inched its way relentlessly up the hill against every type of fire the enemy could pour on it. Yet by nightfall it outposted positions on the summit. This was the culmination of the Division's 12-day battle to crack the Gothic Line. With the fall of Futa Pass, the door, which had been unlocked at Monticelli and swung open by the drives of the 363rd and 361st Infantries, literally fell off its hinge. The Gothic Line had been smashed. "A

Fighting

Team"

In cracking the Gothic Line the Division had fought as a team. Each separate branch of the Army contributed nobly to the accomplishment of the Division's task. The 316th Medical Battalion, its equipment and staff strained by handling thousands of casualties did magnificent work. Litter bearers carried patients over narrow slippery mountain paths, through minefields and barbed wire entanglements and over stream beds. Yet without thought for themselves, the medical men worked to treat the wounded and to evacuate them from the battlefields. For the 316th Engineer Battalion the drive from the Sieve River to the Santerno River was a continuous nightmare. The road net in the Division sector was poor, and damaged by shelling, demolitions, and rain, what roads there were became almost useless. They built roads where no roads were meant to go; they filled or by-passed giant craters; they built bridges and rebuilt them when rain-swollen streams washed them away. By their untiring efforts ammunition, medical supplies and food reached the front-line troops. Much of the credit for breaching the Gothic Line goes to the Division Artillery, composed of the 916, 346, 347, and 348 FieldArtilley Battalions augmented by the power of II Corps artillery. For preparations fired during the campaign the Division controlled 168(*typo?) guns. During the period from 11 September to 22 September, inclusive, 94,379 rounds were fired, and during 3 single twenty-four hour period, 15 September, 14,321 rounds were fired. Again and again prisoners were captured, dazed and stunned by the artillery barrage to which they had been subjected. The heavy artillery fire held the enemy helpless in their emplacements, unable to ward off death or capture by infantrymen with grenades and automatic weapon who swiftly followed up the concentrations. The extensive use of rolling barrages, especia1ly by the 362nd infantry, is a noteworthy application of this technique of advance and an indication of its success in the campaign. The 91st Division was a single, coordinated fighting unit. It was the Division which captured Monticelli and M. Calvi, and fought bitterly for Hills 840 and 844. It was the Division that advanced through rain and fog over steep and rocky terrain along the ridge line of the Apennines to the Santerno River. It was the whole Division which refused to be a holding force, but swept northward along Highway 65 and captured Futa Pass. Great credit is due to the mule pack groups who went where motors could not go; to the 791st Ordnance Company, the 91st Quartermaster Company, the 91st Signal Company, the 91st Reconnaissance Troop, who never faltered and refused to conceive of failure. Each man in the Division had acted as if he had "wanted to win the war all by himself," and the tales of heroism and gallantry are legion. In twelve days it had reduced to nothing a year's work of thousands of impressed laborers and had decimated the best troops Hitler could put into the line against it. |

|

AFTER A BRIEF HALT at the Santerno River during which the Regiments cleaned and replenished their equipment and the troops, so far as was possible, rested and cleaned up, the Division renewed its drive north. The terrain ahead was notably different from what it had fought through. Instead of a range of mountains standing like a wall before them, they now fought on a high rolling plateau from which rose barren rocky mountains with little cover and no concealment. The enemy could be routed from his positions only by clinging to a rock with one hand and prying him loose with a bayonet held in the other. With good enemy observation of the entire Division sector and no covered routes of approach, the naturally defensive features of the terrain made the area stronger, in that respect, than the Gothic Line. Sunny

Italy?

The

strategy

of the enemy was to make each of these mountains a strong delaying

position

while they worked feverishly to strengthen their next main defensive

line,

the so-called Ceasar Line, along an escarpment running east and west of

Livergnano. Thus, the Division's advance became a steady progress

forward

interrupted by short periods of savage fighting, usually centering

about

a town or mountain. On 24 September the 361st Infantry captured M. Beni

and on 25 September the 363rd Infantry captured M. Freddi. Three days

later

the 361st Infantry had seized M. Oggioli, opening the way to an

advance,

slowed only by the fog, to the Monghidoro line.

Thus at the end of 2 October the Monghidoro-Montepiano defenses had been completely overrun. General Keyes expressed his pleasure at the Division’s swift success in overrunning the important positions when he telegraphed General Livesay: of the 91st against a stubborn enemy and despite the adverse elements is a tribute to your fine division."

The

Fight

in the Fog

On the left of Highway 65, the 362nd Infantry fought slowly forward, taking M. Castellari by scaling it with rope ladders on the dark, foggy night of 9 October, and occupying La Guarda. On the right, the 361st Infantry captured Trebbo and pushed under the escarpment at Prato di Magnano. Company I making its way carefully through the fog succeeded in moving behind enemy positions and cutting the highway at La Fortuna, 2,000 yards behind the enemy lines. In the foggy darkness many small parties of enemy were trapped moving down the highway, and either killed or captured. The

Livergnano

Escarpment {See

Map II Corps

Attack

on Livergano Escarpment for Oct 1 - 15}

Only two breaks in the wall existed by which the plateau could be reached. One lay just north of Bigallo and the other was a cut at Livergnano through which Highway 65 runs. Accordingly the 2nd Battalion, 361st Infantry was ordered to move east to the cut north of Bigallo, make its way over this escarpment and then move westward to seize in succession Hills 592, 504 and 481. On the left, the 1st Battalion was ordered to attack Livergnano and neutralize its twin sentinels, Hills 544 and 603. The fighting of the next few days was the most grinding and heartbreaking the 91st Division has ever known. On the right the 2nd Battalion started up the cut north of Bigallo. There was no trail at this point, but it was possible by sheer scaling and climbing to reach the plateau. Riflemen slung their rifles over their shoulders and “hung and crawled with their fingers and toes." The machine gunners disassembled their weapons and each squad member carried parts in his pockets or pack. At one point on the way, Companies E and C had to cross a narrow ledge which the enemy had zeroed in. Only by running a few men across at a time did the companies clear the obstacle and make their way forward. "Little

Cassino"

Once on top of the escarpment near Casole, Companies E and C were fired on and the companies deployed to engage the enemy. While the fight was ill progress the enemy infiltrated around the flanks under cover of darkness, foliage and terrain features, and the companies found themselves located at the bottom of a "tilted saucer" with high ground completely surrounding them and the enemy occupying positions all along this high ground. To assist the push on the right General Livesay ordered the 363rd Infantry committed on the right. Slowly the Regiment fought its way forward, cleaning out pockets of resistance before Bigallo and at Ca Parma and Ca Parisi. During the night of 11 - 12 October, the 1st Battalion scaled the escarpment and reinforced the two companies virtually isolated on the rock rim. While the infantry fought savagely on the ground, the artillery and the air support blasted enemy strong points. The artillery fired 8,400 rounds of all types, most of them in an arc about Livergnano. This artillery power was augmented by position firing by tank destroyers. These blasted the caves and houses of Livergnano and machine gun and mortar emplacements. In the air medium bombers attacked bridges and supply dumps, while fighter bombers flew 250 sorties against troop concentrations and gun areas. On the

Top

Thus at the end of the day, the lines had been straightened and the flanks secured. With Casolina on the left, Querceta on the right and Hill 603 in the center in the Division's hands, the enemy line, referred to by many of the captured prisoners as the Caesar Line, had been overrun and the escarpment had been conquered. Enemy casualties had been heavy, and many prisoners had been taken--225 on 12-13 October. Four

Months

of Combat

But these are only the names the public knows. These are the places the spotlight has caught. But there are hundreds of houses, crossroads, hills and draws where the men of the 91st fought and died to make the capture of more famous places possible. There are miles of road the Engineers swept for mines, scores of streams they bridged or by-passed so the Division could move forward. There are miles of roads, dusty or muddy, frozen hard or running with water over which the service forces brought food and ammunition to the support of the drive. And sometimes there were no roads, and men and mules carried supplies over narrow precipitous trails. Over the same trails and roads the litter bearers evacuated the wounded swiftly and skillfully. Behind these names lies the courage, determination and combat wisdom of each individual infantryman and each individual artillery man. Again and again the story repeats itself: the artillery blasted a path for the infantry, drove the enemy into his holes the infantry followed up to dig the dazed and shaken enemy from the holes. Behind these names lies the skill, the planning, the labor and the courage of every man in the Division. Under

the

command

of General Livesay, the 91st Division has made a name for itself as one

of the great fighting outfits of the Army. It is feared and respected

by

the enemy, praised and admired by its allies. It has been a spearhead

in

every campaign it has taken part in. The 91st Division is a team, a

great

fighting team, of which every man in the Division is a part. It's a

great

fighting Division: it has made history and it will make history until

the

peace is won.

The

End

|

Commanders:

Major General Charles H. Gerhardt

Major General William G. Livesay- 14 July 1943

Col. Rudolph W.

Broedlow - 361 IR

Col. John W.

Cotton - 362 IR

Col. W. Fulton

Magill, Jr. - 363 IR

Lt. Col. James E. Shaw, Jr. - 916 FA

Lt. Col. Calvin E. Barry

- 346 FA

Lt. Col. Woodrow L. Lynn - 347

FA

Lt. Col. Robert B. Collier - 348 FA

Lt. Col. Paul W. Breecher - 316

Medical Btn

Lt. Col. William C. Holley - 316

Engineer Btn

Capt. Gene F. Larrimore - 91 Signal Corps

Capt Clifford E. Lippincott - 91

Recon Troop

Capt Theodore K. Hegner - 91 QM Co.

Capt George R. McDannold -

791 Ordnance Co.

Maj. Alvin W. Laird - 91

Military Police

Units:

361st Infantry Regiment

362nd Infantry Regiment

363rd Infantry Regiment

916th Field Artillery Battalion

346th Field Artillery Battalion

347 Field Artillery Battalion

348th Field Artillery Battalion

Support Units:

91st Recon Troop

316th Engineer Combat Battalion

316th Medical Battalion

791st Ordnance Company

91st Quartermaster Company

91st Signal Company

91st Military Police Company

Attached

Units:

Tank Battalion

Tank Destroyer Battalion

See Organization

Charts of typical Infantry Division

|

|

|

|

| 361 Infantry Regiment |

362 Infantry Regiment |

363 Infantry Regiment | |

|

|

||

| 346 Field Artillery Btn |

347 Field Artillery Btn |

Honors: TO BE ADDED LATER

Casualty Summary: TO BE ADDED LATERGLOSSARY of MILITARY TERMS & ACRONYMNS

Air OP - Airborne observer for artillery, see OP

Art. or Arty. - Artillery

Btn - Battalion, 3 Battalions in a Regiment, consisting of 4 companies each.

Barrage - a concentration of artillery fire power

biv. area - Bivouac area or a rest camp

CP - Command Post, a building or tent where command staff ran the battle

Co - Company. An infantry rifle company consisted of 187 men. 12 companies in a Regiment.

Cubs- light observation aircraft used as airborne artillery observers.

GRS - Grave Registration Servce. Private Brown was in this unit that retrieved and buried the dead.

flak - An anti-aircraft weapon that fired a shell that exploded in air.

KP - Kitchen Patrol

K - Rations - Pre-packaged meals

KIA - Killed In Action

Krauts - American slang for German soldier

Non-Coms - Non-commissioned officers or sergeants

PX - Post Exchange, a store on an army base

OP - Observation Post - position from where forward observer identified targets

SP - Self-propelled artillery.

Ser. Co. - Service Company, a support unit of a Regiment

Livengood,

Roy. Powder River!:

A History of the 91st Infantry Division in World War II.

Paducah, KY: Turner,

1994.

376 p.

Robbins, Robert

A. The 91st Infantry

Division in World War II.

Wash, DC: Inf Jrnl Pr,

1947.

423 p.

Capt. Ralph E.

Strootman, History of the

363d Infantry. Infantry Journal Press, 1947. 354 pages

w/roster.

Weckstein,

Leon. Through My Eyes:

91st Infantry Division in the Italian Campaign, 1942-1945.

Central Point, OR:

Hellgate Pr, 1999. 193 p. D763I8W43.

Reference Material:

"Sheet 98-1 LOIANO"

is a 1:50,000 scale map that includes

the towns along Hiway 65: Sambuco,

Monghidoro, Loiano, and

Livergano.

Dated 14 September 1944.

Reference Maps:

The

Approach to the Gothic Line for a map of the GOTHIC Line

II Corps Attack

on Gothic Line for Sept 10-18

II Corps Attack

on Livergnano Escarpment, 1-15 Oct

Race thru the Po

Valley April 21 - May 2, 1945

|

In two episodes of the TV show “Combat”, the members of Sgt. Saunder’s squad identify their unit simply as “361st”. You can assume they meant the 361st Infantry Regiment. The 1960's TV show followed an infantry squad from the landings at Normandy and through several adventures in France (remember Cage was their French translator). Of course, the real 361st Regiment was part of the 91st Division, which did not serve in France. For

more “Combat”

trivia, click on this external link for the COMBAT

site.

|

Return to Top of PageOther unit histories located on my website:

85th "Custer" Division and associated 310th Combat Engineer Battalion

88th "Blue Devil" Division & 92nd "Buffalo" Division & 1st Armored Division

3rd "Marne" Division & 45th "Thunderbird Division & 442nd Regimental Combat Team

For more on the

various

units of 5th Army, go to Allied

Units & Organizations.