.

History of the

85th 'Custer' Division

Based on booklet entitled:

MINTURNO

TO

THE

APPENNINES

85TH

INFANTRY DIVISION

PUBLISHED BY INFORMATION - EDUCATION SECTION - MTOUSA

PRODUCED BY HEADQUARTERS - 85TH

INFANTRY DIVISION

Passed by Field Press Censor and may be mailed home.

"Minturno

to the Appennines" was a 88-page booklet published by the 85th

Division during the last months of the war for distribution to the

soldiers

and their families. This booklet gives a good overview of the history

of

the 85th Custer

Division.

It contains information on places and events without going into

specific

detail. I plan to post this entire history with sufficient maps to go

along

with the narrative. Refer to monthly Operational

Reports of 328th Field Artillery Battalion for comparison of

events

in this supporting unit.

The booklet abruptly

ends with the fighting at Formiche and Monterenzio on November 22, 1944

--- I guess so it could be published and given to the soldiers.

My

brother obtained a copy of a "supplement"

to this booklet, that continues with the history to the end of the war

in May 1945. This supplement was never published. The

author

and origin of this unofficial supplement is not known but it

follows

the same writing style as the booklet.

This

88-page

booklet contains maps or a photo on almost on every other page.

The

photos are poor quality as the booklet was printed on newsprint.

The maps contain good information of troop movement as it relates to

towns

and landmarks. As my digital drafting improves, I hope to

duplicate

some of the maps to go along with the text.

LEGEND - In

the

following text, the names of units are color coded. My comments are in

{brackets}.

American

Units

=

American, British and Allied units are highlighted in dark blue.

Since this is about 85th Custer Division, all references to regiments

and

units are not color coded. The exception to this is

the

companies are in bold to allow ease of reading.

German Units=

Enemy units are highlighted in Prussian blue.

Gothic Line=

Enemy defense lines, towns, and geographical places are in deep red.

{ My comments}

=

My notes and comments in blue brackets.

CONTENTS

FORWARD -

Major General

John B. Coulter (Not Included)

INTRODUCTION -

General

Mark Clark (Not Included)

EARLY HISTORY -

A

Brief history of WW1

TRAINING FOR THE SECOND WORLD WAR

THE GUSTAV LINE -

Minturno, May 1944

THE SECOND PHASE

THE DRIVE ON ROME AND TO THE NORTH

- May, June, July 1944

BETWEEN ATTACKS

THE GOTHIC LINE

-

September 1944

MORE MOUNTAINS

"SUPPLEMENT"

THE LUCCA

PLAIN

AND THE SILLARO VALLEY

THE LAST

ATTACK

THE PO VALLEY CAMPAIGN

WINDING UP

Map Index - Map sketches from

the booklet

were created. GO TO MAP INDEX

Organization

Chart and list of units within the 85th Division - Organization

Distinguishing

Unit Insignias of units in the 85th Division - DUIs

THE EARLY HISTORY

It

was in another war against the Germans that the Division was first

established

as part of the National Army, on August 25, 1917. Organized at Camp

Custer, Michigan it became known as the Custer Division.

After nearly a year's training, the Division

embarked

for England. From here the 339th Infantry Regiment, with

attached

engineer and medical units, was shipped to Russia where it participated

in bitter fighting against the Bolshevik Revolutionary Army. The

remainder

of the Division was moved to France where individual organizations

supported

the IV, V, and VI Corps. In France the Division served primarily as a

replacement

depot division, furnishing some 20,000 replacements to other

organizations.

Several units, however, remaining intact---the 160th Field Artillery

Battalion,

the 310th Field Signal Battalion, the 2nd Battalion, 310th Engineers

and

the 310th Ammunition Train - saw action on the Western Front, in

Lorraine.

in the St. Mihiel operation, and in the Meuse-Argonne sector.

At the close of the war parts of the Division served

in Germany in the American Army of Occupation. By August 1919, however,

the last elements of the Division had returned to the United States.

Shortly after this the Division was

inactivated.

During the years of peace that followed it continued to exist in the VI

Corps Area as a Reserve Division with Reserve Officer personnel.

WW1 Uniform of a 'Custerman'.

Originally, WW1

patches

were sewn into a square piece of khaki.

TRAINING FOR THE SECOND WORLD WAR

In

January, 1942 the War Department ordered the reorganization of the 85th

Division as a triangular unit{*}. The

Division

was reactivated at Camp Shelby Mississippi on May 15th.

Brigadier

General Wade H, Haislip was designated as the Commanding General,

becoming

Major General Haislip shortly before assuming command. The Official

Mobilization

Training Program was begun early in June. In January, 1943, the first

programs

were undertaken in the training of Combat Teams, as the next step in

developing

the coordination of all the elements of the Division in preparation for

combat. {* A triangular unit meant the

divisin

had 3 regiments; 337th, 338th, & 339th. Each regiment had

three

battalions, consisting of four companies, each.}

On February 21st {1943} Major

General Haislip became the Commanding General, XV Army Corps, and

Brigadier

General John B. Coulter, the Assistant Division Commander,

succeeded

him as the Division Commander. On March 12th Brigadier General Coulter

was promoted to the rank of Major General. On March 18th Colonel Lee

S. Gerow was promoted to Brigadier General, and became the

Assistant

Division Commander.

A publicity shot of

General John

Coulter, commander of 85th Division throughout

the

War.

Early in April the Division began its

move

to the maneuver area near Leesville,

Louisiana.

Here for 2 months the conditions of combat were simulated,

division

fighting against division much of the time. In June the Division had

completed

its training in this area, and then moved to Camp

Pilot Knob, California, where it began still more arduous

training

in the Desert Training Center. In August the Division was moved to Camp

Coxcomb, California where desert training was continued

until

October. This training was brought to an end by orders transferring the

Division to Fort Dix, New Jersey,

the

last move before shipment overseas. At Camp Coxcomb, Brigadier General Pierre

Mallett became Division Artillery Commander, succeeding

Brigadier

General Jay W. MacKelvie, who had been with the Division since

its

activation but was now transferred to the command of XII Corps

Artillery. {The

Division

went desert training because the Allies were still fighting the Germans

in North Africa. Go to Desert

Training Center for

Map of these camps & history & photos.}

At {Fort}Dix

{NJ}

the final preparations were made for entrance into combat. On December

16th the Advance Detachment of the Division set sail for Africa. A camp

was established south of St. Denis Du Sig on the northern coast of

Algeria,

near Oran. The remainder of the Division sailed in December and

January.

By mid-January the entire Division had been assembled and was

undertaking

a program of intensive training in mountain warfare. Early in February

the Division moved to Port-Aux-Poules for a period of amphibious

training.

While here the first orders were received to alert the units of the

Division

for movement to Italy. The 339th Regimental Combat Team was

the first to be moved. Arriving in Italy on March 14th, it was attached

to the 88th Infantry Division

and became the first regiment of the Division to see combat in the

present

war. Shortly afterwards the other units of the Division reached Italy,

landing at Naples, and the final

preparations

were made for the Division to go into the line near Minturno,

about 40 miles to the north.

Members of a

Heavey Weapons

platoon with a 37mm gun at Camp Shelby.

|

|

A group photo

taken at

the Desert Training Center in California.

|

|

THE GUSTAV LINE

At

8 o'clock on the morning of April 10th {1944}the

Division was committed to action as a unit for the first time in its

history.

In the left sector of II Corps zone the Division took up position a few

miles north of the Gargliano River along a low ridge of hills facing

the

Gustav Line. The front extended from the Ryrrhenian Sea on the sough,

north

along the low hills beyond Minturno to the Ausente River. The 339th

Infantry (with Companies L and M of the 338th

attached) moved up first to hold a front extending 5500 yards in from

the

sea, with 3 battalions abreast. By April 14th the 337th Infantry

had taken over a 4000 yard front, on the right of the 339th,

extending to the Ausente River. One platoon of the 85th Reconnaissance

Troop was placed as a guard over the bridge across the Gargliano, about

2 miles southeast of Minturno on the site of the ancient town of the

same

name. All the traffic to our forward areas was obliged to use this

bridge,

which thereby became a point of vital importance to the Division. The

remainder

of the Troops patrolled the coast, on the watch for any attempts by the

enemy to encircle the Division flank by an amphibious operation and to

apprehend agents landing by boat. While holding these positions the

Division

prepared for the May offensive.

The Tyrrhenian Coast runs west from Minturno

and

Scauri to Formia. About a mile beyond Scauri is the Croce Road Junction

where the road south from Cassino joins Highway 7 about 6 miles above

the

Minturno Bridge. West of the Junction the Highway for 5 miles crosses a

narrow plain, dominated by Monte Campese, to Formia where the mountains

come down to the sea. At Formia the Gaeta Peninsula juts off to the

south,

but the Highway cuts sharply northwest across the mountains to Itri and

Fondi, at the northern limit of the Fondi Plain. At Fondi the road

turns

southwest, crossing level plains for 5 or 6 miles. Then, skirting the

mountains,

it continues some 5 miles more to Terracina, built between high rocks

and

the sea.

The Gustav Line

was anchored on the beaches near Scauri and in the low hills rising

from

the Capo D'Acqua at the base of the Aurunci Mountains. Once the Gustave

Line should be broken the efforts of the advance would ultimately be to

secure Highway 7 as far as Terracina.

The enemy -- consisting cheifly of elements of

the German 94th Infantry Division

--

was dug in along the western anchor of the Gustav

Line. His positions extended from the coast near Scauri,

north

across the low hills of Colle San Martino, then northeast across the

Solacciano

Ridge to Santa Maria Infante. Between ours and the enemy's lines was a

narrow grassy valley which was less than a half mile wide.

Our troops were dispersed in fox-holes, behind

rocks, and in buildings. Outposts were established a few hundred yards

ahead of our forward positions. Some of these were used as waystations

for the patrols as they went out and came back. Some had names --

"Ferdinand's,"

"Snuffy's", "Mother's Place."

Every night for a month each battalion sent

over

one or more patrols, and on the basis of the patrol reports and aerial

photographs taken from Cub planes and P-38s, we learned the location of

many enemy positions. On this sector of the Gustav

Line most of the enemy positions were on the reverse slopes

of the hills. On the forward slopes there were minefields and wire

barriers,

placed in such a way that men advancing up the hills, feeling out the

unobstructed

passages, would come to points on the crest where they would be met by

interlocking bands of fire from the machine guns in their positions on

the reverse slopes. From the higher hills behind the first ridges the

artillery,

mortars and self-propelled guns were in position to blast at any of our

troops coming down to attack the dug-in positions.

Minturno, the Bridge, Tufo, and Tremensuoli

received

harassing fire regularly. The main street of Tremensuoli was nicknamed

"Purple Heart Alley," and it is reported that troops stationed in

Tremensuoli

had figured out that a man could appear on that street for no more than

20 seconds before drawing fire.

The important fact concerning the enemy's

defenses

in the coastal sector was that he expected an attack from the water.

Along

the beaches there were thousands of mines, dense barriers of concertina

wire, concrete posts to block landing barges and tanks, and elaborate

concrete

pillboxes. Along the entire Gaeta Peninsula were batteries of coastal

guns.

Many of these defenses had been erected by the Italians and the Germans

had added their improvements. But although the enemy's preparations to

meet an attack from the sea were elaborate, it was soon to be found

that

the defenses of the Gustav Line

were

equally formidable.

Through April and the early part of May the

artillery

supporting the Division fired constantly against enemy movements and

artillery

positions. From the very beginning the policy was established of firing

about 5 rounds for every German shell. Our superiority in thei respect

compelled the Germans to remain in their dugouts througout the day,

restricting

all their movements to the hours of darkness.

The weather was fine. On the steep crags of

the

Petrella Mountain Mass to the north there was still snow, but around

Minturno

the valleys and hills were green with new growth.

Mist sometimes settled down, and sometimes at

night fog came in from the sea. But already the white dust was thick on

the roads, not to be laid by rain till another autumn.

On April 24th the 338th Infantry relieved

the 339th along the coast, while that regiment took a short

rest. Then, as plans for the attack matured, the 339th returned

to the line to take the left half of the 338th sector in from

the coast with 2 battalions in the line. Two battalions of the 338th

now held approximately one half of their former regimental sector. The

337th Infantry was meanwhile relieved by elements of the 88th

and became the Division reserve in an area southwest

of Tremensuoli, except for the 3rd Battalion which was attached at this

time to the 339th Infantry. Attached to the Division now

were

the 756th

Tank Battalion, the 776th

Tank Destroyer Battalion,

and the 5th

Italian Mule Pack Group. The artillery remained under

Division

control and received direct support of the big guns of the Corps

Artillery, as well as the entire 36th

Division Artillery.

Along

the Division front the night of May 11th {1944}

there was no moon and enough layers of mist in the upper air to obscure

the stars. In the dark, along the entire line, from the Tyrrhenian Sea

through Cassino to the Adriatic, men waited to attack.

At 11 o'clock{pm}

the great artillery barrage began. Long Toms, the great 240mm guns,

75mm

pack howitzers, cannon, British 6 and 25 pounders, 105's, 155's,

everything

let go at that moment. For a full half-hour shells were poured into the

German positions, tens of thousands of them. Almost nothing could be

heard

but the thunder of guns, and the air was lit up by the flashes of the

powder

charges. From the Minturno Hill, Scauri could be seen as it by daylight

and in flashes they valley and the enemy's hills came into clear view

out

of the darkness.

The infantry moved up to the edges of the barrage. As the

guns

ceased firing, companies, platoons and squads advanced slowly into the

fire that immediately met them.

GO TO Map

1 – Attack on Gustav Line - May 12-14, 1944

On the right, the 338th moved out to attack the

Solacciano Ridge. The 339th on the left attacked the

Domenico

Ridge, the low hills extending to its left, and Celle San Martino, made

up of Hills 66 and 69.

The enemy apparently did not expect an attack at this time, but after

the

initial surprise he recovered from the shock of the bombardment and

held

firm.

What was beginning now was a bitter up-hill

fight

across exposed slopes, almost every move made under the eyes of the

enemy.

There could be no let-up in the assault once it had begun, and as we

came

to grips with the enemy in his closely-crowded positions the fighting

went

on without pause day and night. It took time to get through the

minefields

before the dug-in positions could be reached, and in that time the

enemy

let go with his machine guns and mortars, covering every approach. A

small

stream, the Capo D'Acqua, proved one of the most bitter obstacles.

Troops

struggling through its current and up the steep banks which tanks could

not climb advanced into the direct fire of machine guns and mortars

"zeroed

in" on them.

Attacking towards the Solacciano Ridge, the

338th

ran into fire from thick-walled farm houses the enemy had fortified,

and

in approaching these the troops made their way through the most densely

laid minefields of all. Troops of I company drove the enemy from

one of these houses, and waited while the artillery leveled a

neighboring

house occupied by the enemy. Then they took over the fortified

positions

in time to meet the reinforcements the Germans sent to take the houses

back. Attacking in the draws a platoon of A Company lost man

after

man to machine gun fire until it was able to close in and destroy the

enemy

with hand grenades and bayonets.

The 339th was meeting the same kind

of fierce resistance. Advancing along the low hills of the Domenico

Ridge,

one platoon lost several of its members in the minefields and still

others

to machine gun fire. When the rest reached their objectives and dug in,

the enemy counterattacked. Word was received by radio that our men were

surrounded, and after that no messages came back. When the hill was

recaptured

2 days later, the bodies of the leader and 5 of the men were found. At

another point the bodies of most of the members of a platoon of B

Company were found surrounded by 35 dead Germans.

In the bitter fighting several companies were

reduced to 50 or 60 percent of their strength. The reinforcement coming

up through the minefields, which could be cleared only slowly and in

the

dark, suffered heavily from the mines and from artillery fire the enemy

laid down to cut them off. The first ridges were to be taken only at

heavy

costs.

The

fighting was as brave as it was fierce. Company G, 339th

Infantry was cited the the President for its outstanding performance of

duty during this period. In advancing towards its objective, the

Company

took advantage of the artillery barrage to seize part of a hill before

the barrage ceased. The 2 assault platoons, closing with the enemy

before

he could recover, killed 60 and captured 40 of their defenders,

demolished

8 bunkers, reduced 7 pillboxes, and captured 25 automatic weapons. The

objective taken, the company immediately used the enemy weapons to

assist

the assaults of adjacent companies. Meanwhile the company's own

positions

were pounded by artillery and mortar fire for 48 long hours. The enemy

counterattacked 3 times, and was repulsed each time though our

casualties

were increasingly heavy and no reinforcements could be brought up. For

36 hours the men were without food or water, but they held out until

the

advance on other parts of the line made their position secure.

It was in the first day's fighting that Lieutenant

Robert T. Waugh, leader of the first platoon of this company{G},

engaged in the beginning of a series of actions that was to win him the

Congressional

Medal of Honor for conspicuous gallantry. He reconnoitered a

minefield before entering it with his platoon, and then directing his

men

to fire against 6 bunkers, he advanced alone against one position after

another. Reaching the first bunker, he threw phosphorous grenades into

it, and as the defenders came running out he killed them with a burst

from

his tommy gun. Then he passed on to each of the remaining 5 bunkers,

killing

or capturing all of their occupants.

The attack of the 3rd Battalion of the 339th

Infantry

against Hill 66 and Hill 69,

the Colle San Martino, met perhaps the fiercest resistance of all. At

the

very beginning a squad of L Company was destroyed by artillery

as

it passed through Tremensuoli towards Hill 113 East. Following the

trail

out of the town still another squad was wiped out by the enemy

artillery.

But the remainder of the company and the battalion pushed on across the

Capo D'Acqua to the slopes of Hill 69. Bitter fighting raged through

the

night as platoon after platoon moved up, but by 5 o'clock next morning

the hill was captured.

May 12th and 13th passed in an unceasing

struggle.

The gains were small, and fiercely won. Wherever we moved the enemy

threw

in heavy, accurate fire, and every break we made in his lines he tried

to repair, counterattacking with all the strength he could collect. K

Company of the 337th came up on the 12th to attack Hill 66, but by the

time it reached the base of 69 it had suffered such heavy losses that

it

could not continue. It then dug in to reinforce the troops of 69.

And at 9 o'clock that morning the nemy sent down 200 men and a tank to

drive us out. He failed. But it was certain that still other attacks

were

being prepared and the need to capture Hill 66 became more urgent. So

the

1st Battalion of the 337th was brought up under cover of a smoke screen

to pass through the exhausted 3rd Battalion of the 339th. {For

more details of the fighting and casualties on Hill 69, go to webpage

on Biography

of Private Patterson;

a member of Company K, who was killed in action during this combat.}

GO TO Map

2 – From Minturno to Piverno & Sezze (Part 1)

-

May 11- 28, 1944

The fresh battalion pushed on slowly over Hill

69, and began its attack on Hill 66 at 4:30 the afternoon of

the 12th. The enemy who had seen our troops advancing met them with

such

heavy fire that they were soon driven back. But the withdrawal was made

only in order to reorganize. Twelve battalions of II Corps Artillery

now

laid down a barrage on 66, and the infantry moved out again at 6:30.

The

opposition was still stubborn, but the enemy soon had all he could

take.

Colle San Martino was captured, and our troops immediately consolidated

their newly won positions.

The next morning the enemy counterattacked.

Fifty

men firing machine pistols stormed the hill. They came within 50 yards

of our positions unopposed. Then the order to fire was give, and every

man of the enemy group was killed. Later others tried it again, and met

the same results. Company C of the 337th Infantry received a

Presidential

Citation for its performance of duty in this action.

On the 13th the enemy was counterattacking

everywhere,

and all along the line the men fought bitterly to hold their gains. And

they continued to push slowly ahead. Gradually the sum of the gains

became

more important. By the morning of the 14th we held Hills 79 and 69 and

several positions on the Solacciano Ridge. Troops were ready to move

into

Scauri. It now remained to reorganize for the final breakthrough. The

2nd

Battalion of the 337th came up to attack between the 338th

and 339th. On the afternoon of the 14th supported by tanks,

they attacked Hill 108, overrunning it and taking more than 80

prisoners

and the 338th was clearing the last enemy resistance on the

Solacciano Ridge.

By noon of the 15th the 339th was holding

Hills 66, 79

and 58; the newly committed 2nd

Battalion

of the 338th had captured the Cave D'Argilla area; and the

337th

was on 108. The last

counterattacks

had been beaten off. The Gustav Line was broken. The drive which was to

secure Highway 7 to Terracina was now to begin.

THE SECOND PHASE

The

coordinated Division attack began on the afternoon of May 15th.

The enemy had a secondary line between Castellonorato and Scauri, and

the

Division prepared to attack before the enemy had time to get set. The

338th

Infantry was ordered to strike wet to seize Monte Penitro, then

to drive southwest to the Croce Road Junction and on to Highway

7. If successful this attack would by-pass Scauri and Monte

Scauri on the jut of land west of the Highway. On the right the 337th

Infantry was ordered to seize Castellonorato, and then push

west

along the mountain road to Maranola, a distance of about 5

miles,

prepared to turn south there, following the road leading to Highway 7

just

below Formia.

By this time the 88th

Division on the right, with the assistance of the 338th

Infantry, had reduced the important enemy strong-point in Santa Maria

Infante.

In order to coordinate the advance of the 2 division the 349th

Infantry Regiment of the 88th

Division was now attached to the 85th. Attacking

west form La Civita, on the mountains north of Castellonorato, this

regiment

was ordered to strike due west across the roadless mountains parallel

to

the advance of the 337th.

The enemy apparently relied on the extremely

rugged,

mountainous country to hold up our advance. He had neglected to

construct

any considerable number of defenses, though hasty positions served him

well, and from the positions on Monte Campese and with the support of

guns

on the Gaeta Peninsula he was attempting to cover the withdrawal of his

troops to Formia. Guns on Monte Penitro and Tripoli were being used to

delay the advance of our troops on Castellonorato and beyond. {

My father reported he obtained the German camera in Formia on

May

15th. Refer to Photos

from the Italian Front

for photos and story about this camera.}

There was little attempt to defend the first

hills.

The 3rd Battalion of the 337th Infantry, relieved

from attachment to the 339th, and shifting over to take up positions

on the left of the 2nd Battalion, came under fire from Monte

Penitro, but they went on, the companies in lines of squad columns, and

Castellonorato was captured by dark. The enemy was now withdrawing all

along the line. He abandoned Monte Scauri when our seizure on the 16th

the 339th moved into the town of Scauri and cleaned out a

few

delaying positions on Monte Scauri.

Advancing from Penitro towards the Croce Road

Junction the 338th Infantry washeld up by the last counterattack

in this area. The enemy was trying to save the remnants of his forces

now

deeply outflanked by the 88th

Division

driving west across the mountains north of the Formia corridor. By this

time the 94th Division

had

been reduced to approximately 1200 men and to save these the enemy

threw

in a battalion of impressed foreign laborers and some troops from the 274th

Grenadier Regiment, attacking from the banks of the

Aquatraversa

stream. He also brought to bear concentrated artillery fire from Monte

Campese and Gaeta. This held the

regiment

up during the 16th, but by the end of the day that resistance was also

overcome.

On the 16th, the 2nd and

3rd Battalions of the 337th advanced to the west

beyond Castellonorao, crossing the Aquatraversa, and moving towards

Maranola.

One company of the 3rd Battalion, as it came close to Monte

Campese, received heavy mortar and automatic weapons fire. Its troops

then

dug in at the base, awaiting the arrival of the remaining companies who

also dug in before renewing the attack. But next morning they found

that

the bulk of the enemy had withdrawn. It only remained for the 3rd

Battalion to clear the pillboxes and sniper posts on the heights while

the 2nd went on to capture Trivio and Marnola.

The

enemy resistance had now cracked everywhere. The enemy had neither the

fores nor the time to establish a line in front of the Division.

Elsewhere

he had also been defeated. The last desperate resistance on the central

Italian front at Cassino was to be

wiped out on the 18th, and on the west the final push was

under

way to join with the forces from Anzio

Beachhead.

On May 16th the 85th Division was placed on a

72-hour

alert, prepared to move to Anzio by water, but is soon appeared that

the

joining of the forces would be achieved sooner than had been originally

expected. The final decision was that the Division would continue its

drive

towards Terracina.

{The

amphibious

landing at Anzio

in January 1944 was supposed to relieve the pressure off the Cassino

front.

However, the Germans resistance kept the British and Americans confined

until spring. The Allied commanders came close to pulling the

troops

out of Anzio.}

Now that Campese was taken, the last major

obstacles

in the advance of the 338th on Formia had been

removed.

On the 17th the regiment advanced into the town,cleaning out

the little remaining resistance the next day. Late in the night of the

18th the regiment moved out of Formia to capture Monte

Conca.

In doing this they opened the road to Itra, and arrived at positions in

the rear of the enemy defenses on the Gaeta Peninsula. On the 19th

the 338th Infantry and the 85th Reconnaissance

Troop

cleared out a few pockets of resistance in the Peninsula with little

difficulty,

and troops entered the town unmolested. The enemy's next refuge was the

so-called Hitler Line, anchored at

Terracina.

The 339th Infantry had now come up

from the vicinity of Scauri along the Highway to Formia, where it began

to advance along the Highway to Itri.

Seizing mountains on the left of the road--Monte Cefalo and Monte San

Onofino--the

regiment was for a time harassed by fire coming from Itri. The 2nd

Battalion was dispatched to clear the enemy forces from a section of

the

town, and accomplished its mission in short order.

In Formia, Gaeta and Itri the enemy had left a

large amount of valuable equipment behind, and it was apparent that he

had been forced to withdraw in haste. Along the roads there began to

appear

the debris of a defeated enemy --unpacked boxes of ammunition, unlaid

mines,

discarded gas masks. Later there was to be the much more impressive

litter

of a rout, but now ere the first signs of a serious defeat.

At

this time a pursuit force was organized to hound the retreating

Germans.

The 2nd Battalion of the 337th Infantry was

motorized,

operating with a company of tanks, a platoon of the 85th

Reconnaissance

Troop and a platoon of engineers. This force detrucked at Itri, and

moved

over to the base of Monte Cefalo where it prepared to attack Monte San

Biagio which descends to the northern edge of Highway 7 at the Fondi

Plain.

The remainder of the regiment went into a reserve status for a brief

period.

The 339th Infantry now began an

arduous

advance from the vicinity of Fondi, lately captured by elements of the 88th

Division, crossing steep, almost trailless mountains north

to

Sonnino, a distance of 12 miles. The troops struck out across this

rocky

country, following the compass, and their supplies were brought to them

by mules and by men carrying rations and ammunition on their backs.

The regiment possessed almost no knowledge of

the enemy's dispositions in this area, and contact with the Germans was

temporarily lost. The 94th Division

was nevertheless known to be in desperate need of reinforcement as it

retreated

in to the mountains north of Fondi and along the Highway to Terracina.

Between San Biagio and Sonnino there were 3

mountains

in a direct line, each more than 1500 feet high. The 1st

Battalion

moved ahead first in the advance on Sonnino. The 2nd

following

the 1st was obliged to clear out several enemy bands as it

climbed

the high ground overlooking Highway 7, and its advance went slowly. It

was not before the morning of the 23rd that all these

pockets

had been cleaned up. Shortly before noon of that day the 1st

Battalion had come into positions for the attack on Sonnino, but before

the 2nd Battalion had come abreast of it enemy anti-aircraft

guns opened up on both battalions. As our own artillery had been

outdistanced

it could not lend support to our infantry. Nevertheless, preparations

for

the attack continued, the 2nd Battalion took positions on

high

ground from which it could lend supporting fire, the 3rd

Battalion

by now had joined the 1st, and the attack jumped off at

half-past

four. The advance went ahead steadily, and after 2 hours' fighting the

town was ours. In addition to killed, the enemy lost 73 men as

prisoners.

One of these was the commander of the 3rd Battalion of the 15th

Panzer Grenadier Regiment who said that our troops had not

been

expected to cross over the mountains and that the first intimation he

had

had of our presence was when he suddenly received a message that he

Americans

were on both flanks and that retreat was impossible. {Typo?

Maybe 16th Panzer Greadier Regiment.}

Meanwhile, on May 21st, the 337th

Infantry had been recommitted, and, passing to the rear of the 339th,

advanced on the left flank of that regiment to take Monte San Biagio,

where

it found little resistance though it captured a considerable number of

prisoners.

The 338th had enjoyed a short rest

after mopping up Gaeta. Billeted briefly in what remained of the villas

along the coast, the troops had a chance to swim in the salt water, get

a change of clothes, and replace damaged equipment. On May 21st,

however, orders were received to move on to take positions west of

Fondi

to begin the advance on Terracina.

Highway

7 is the single road serving several of the II Corps units, and from

the

Croce Road Junction on there was a solid mass of traffic. The long

lines

of supply trucks and artillery, the battalions of foot troops, the

tanks,

the reconnaissance cars, the liaison jeeps, all created the picture of

a great military action and its vast momentum. Partly to avoid delays

caused

by the road traffic, the 1st Battalion of the 338th

moved by water in DUKW's (two-and-a-half ton amphibious trucks) to

Sperlonga,

about 12 miles west of Gaeta. They were prepared to find enemy on the

beach,

but when they arrived they discovered that the Germans had already

pulled

out, and the battalion proceeded immediately by DUKW and on foot to

join

the remainder of the regiment near Fondi.

In the meantime the 337th Infantry

was crossing the mountains and following the highway southwest towards

Terracina. Along the entire Division front the enemy resistance

stiffened

as the strength of th eGerman reinforcements made itself felt. Both the

337th and 339th Regiments were now encountering

troops

of the 29th Panzer Grenadier

Division

and still other forces hastily withdrawn from Anzio and thrown into the

defense of Terracina.

Pushing over the mountains northwest of that

city

the 337th Infantry captured Monte Autone and Monte Copiccio

on

May 21st after much weary climbing. By taking these

positions

they cleared a long stretch of Highway 7 and the 1st

Battalion,

with strong armor support, now moved down the Highway until they ran

into

heavy fire covering the defile between San Angelo and the sea. Several

truckloads of enemy troops had been rushed to the end of the Terracina

Aqueduct, where they occupied prepared positions. Here the fire from

small

arms and mortars stopped further passage along the road.

Troops and trucks were lined up in the bright

daylight waiting for the artillery to be brought up to wipe out the

resistance.

The enemy guns had already been pulled out as had most of his mortars,

and the advancing forces halted just out of range of small arms fire,

where

the enemy could see them but could do little. When heavier guns were

brought

up, the Germans were put to flight and the advance continued.

Further, more serious opposition was met on

the

outskirts of Terracina. The point of the march column was within 500

yards

of the city when the enemy opened up on it with automatic small arms

fire.

The beach on the left of the road was known to be mined and on the

right

the enemy had dug in on the steep bluffs. Tanks were sent ahead, but

these

were halted by a crater road block. There was nothing to do for the

moment

but withdraw, and the battalion now took up positions on the northern

and

forward slopes of Monte Croce.

When the sun came up in the morning the troops

discovered that the crest of the mountain was held by large groups of

enemy.

Throughout most of the day the battalion was pinned down by fire from

here

and by numbers of roving snipers with machine pistols. The snipers were

disposed of by patrols, and in the late afternoon the battalion moved

to

the reverse slopes of the mountain where the enemy in his fixed

positions

could not reach them. A rolling barrage was called for, covering the

crest

of the mountain yard by yard, and in a short time the positions on

Croce

were wiped out.

The 3rd Battalion, coming up along

the right of the 1st, had also been troubled by fire coming

from Monte Croce. Climbing through heavy brush on the steep slopes of

Monte

Stefano, they were supplied only by mules and hand carry. But during

the

night of the 22nd and the early morning of the 23rd

the heavy weapons elements were brought up, and the battalion moved

forward

over the rocks, firing every weapon it possessed against the strong

points

on the slopes of Croce opposite them. When the enemy was finally wiped

out by the artillery, the 3rd Battalion had reached

positions

from which it could overlook Terracina. Meanwhile the 2nd

Battalion

had moved through the 1st, prepared for a coordinated attack on

Terracina

with the 3rd Battalion on the morning of the 23rd.

GO TO Map

3 – From Minturno to Piverno & Sezze

(Part

2) - May 11- 28, 1944

The

battle for Terracina developed into a battle for the cemetery

on

the outskirts of the city. This cemetery was on high ground and the

approaches

were rocky and steep. A light rain had made the slopes slippery and

this

hindered the tanks, bu texcellent close support was rendered the

infantry

by several battalion of self-propelled 105's*

belonging to the 6th Field

Artillery

Group. In the cemetery the enemy had dug in beneath the

tombs.

Machine guns, mortars and snipers were using the monuments for cover.

The

battle raged the entire day, but just before dark the last enemy

resistance

had been overcome, and by midnight the 2nd and 3rd

Battalions had taken up positions on the edge of the town. *{105's

- This self-propelled gun was a 105-mm howitzer mounted on a mobile,

armored

car. The term, "self-propelled gun", generally refered to an

artillery

gun mounted on a tank chasis that didn't have a transversing turrent. }

Meanwhile the 1st Battalion had

reorganized

and moved over on the right to the northwest of Terracina. All during

the

night our artillery fired into the roads leading to the north, and what

was left of the once beautiful city crumbled. After dawn the battalions

moved easily into the town. The bottleneck, Terracina, was captured,

and

the road to the Anzio Beachhead was opened.

To assist the fighting around Terracina the 338th

Regiment had been ordered on the 22nd to move out and

capture

the mountains on the right of the 337th in order to outflank

that city. At the beginning of the advance a brief encounter occurred

at

the southern end of a 5-mile long railroad tunnel. The Germans used

this

tunnel as a protected route of supply and evacuation and through it had

been coming some of the badly needed reinforcements. Emerging from the

tunnel and preparing positions these troops were surprised by our

advancing

forces. After our supporting air units had blocked the northern end of

the tunnel by bombing, tank destroyers and reconnaissance troop weapons

fired directly into the mouth of the tunnel. Stories of what happened

here

spread everywhere, and were multiplied in the telling. The essential

point

was that the tunnel was no longer of any use to the Germans. After this

initial engagement the 3rd Battalion of the 338th

Infantry, reinforced by elements of the 776th Tank

Destroyer

Battalion, remained on guard near the tunnel to make certain

that none

of the enemy escaped, and other elements of the regiment went on to

capture

Monte Leano and Monte Nero with little difficulty.

The enemy was now withdrawing from Terracina

along

the Highway on the edge of the Pontine Marshes, which he had flooded,

and

beyond Sonnino he was withdrawing northwest across the Amaseno River.

The

pursuit continued.

Our advancing troops now saw more and more of

the results of the work done by the artillery and the air forces. The

Germans

had been compelled to give up their policy of moving only at night, and

in their need of getting out they had taken to the roads in daylight

despite

our overwhelming air superiority. This decision perhaps saved them from

complete destruction, but it was nevertheless a ruinous escape. Burnt

out

trucks and tanks were everywhere, abandoned spiked artillery,

ammunition

dumps, and the bodies they had not had time to bury.

The problem now was to keep contact with the

enemy.

Dismembered and defeated, his organization fell apart, and the signs of

confusion spread everywhere. By May 26th it seemed that

almost

all traces of a coherent organization had disappeared. Instead of

fighting

by platoons, companies and battalions, the enemy now threw together

so-called

"Battle Groups," miscellaneous troops gathered wherever they could be

found,

put under an officer or an NCO and thrown into the line. Since May 22nd

the enemy had had almost no artillery support. His scattered foot

troops

received only the occasional aid of self-propelled guns and a few

machine

guns hastily dug in in pockets of hills. Contact was consequently

maintained

only with a few delaying forces.

The Division now pressed forward with all

possible

speed in the hills north of the Pontine Marshes. During the 25th

and 26th it had advanced west of the Abbe di Fossanuova and

Priverno. At this time the 338th was marching in a column of

battalions, meeting practically no resistance until it arrived at an

impromptu

enemy line in the hills east and northeast of Sezze. Monte Trevi was

quickly

seized, and the last resistance in Sezze was mopped up by elements of

the

regiment after the town had been entered by troops of the 117th

Reconnaissance Squadron. The 338th Infantry was

advancing

northwest towards Monte San Angelo, when on the 27th it was

relieved by the 351st Infantry

Regiment

of the 88th Division.

By now forces pushing out from Anzio Beachhead

had joined with other Allied units coming from the east. As a result

the

85th Division had been "pinched out." After 49 days'

continuous

service in the line the Division passed to reserve, moving to Sabaudia,

formerly a resort on the coast below Anzio.

Between May 11th and 28th

the Division had broken the Gustav Line

and driven the enemy before it 45 miles over a long series of rugged

mountains.

It had routed the Germans, destroyed enormous amounts of equipment, and

had taken 1173 prisoners. Victory was in the air.

THE DRIVE ON ROME AND TO THE NORTH

Along

the entire front the advance of the Allies was rapidly accelerating.

The

enemy was on the point of rout, and the pressure of the pursuit needed

to be intensified; Rome and the destruction of the enemy were almost

realized

objectives. Accordingly, orders were now given to move the Division

north.

east to the Lariano-Guilianello sector. The Division took up its new

sector

on May 30th.

In Lariano and the hills to the north the

enemy

still manned a defensive line. In positions here the famous Hermann

Goering Panzer Grenadier Division hoped to delay our advance

sufficiently to permit the escape of other troops along the roads.

While

the positions they held in the vicinity of Lariano, though few, were

well

prepared, beyond that locality the Germans were compelled to erect only

the hastiest kind of field fortifications, hurriedly cutting down trees

to clear fields of fire and to provide tank barriers. {Hermann

Goering Division - an elite panzer division formed from the

Luftwaffe.

In the 1930's, Herman Goering was chief of Police and he formed a

police

brigade that bore his name. As this unit grew, it became an

anti-aircraft

unit for Hitler's Wolf Lair and then a regiment and eventually a panzer

division. The literal translation of their name was 'paratrooper tank

division'.

It served in Sicily and in Italy until its departure in July 1944.}

But now the sense of conquest had grown

stronger

among the troops, and every step meant that Rome was that much closer.

There was still the ugly job of destroying the snipers lurking in the

brush

and woods, the machine guns placed in the railroad cuts, and still at

night

the occasional German planes came over to harass the troops. But miles

now were being covered each day, and the advance was accelerated. The

service

companies and the rear command posts had more and more difficulty in

keeping

up with the troops. The weather continued bright, and clear. Everywhere

the trees were growing greener- poppies were thick in the fields, and

around

Cori the cherries were ripe.

The new Division sector lay between 2 great

highways

leading to Rome. About 5 miles north of Lariano Highway

6, from Cassino, came into Rome from a southeasterly

direction.

About 4 miles west of Lariano was Highway 7,

leading to Rome from the south. The route of the Division advance lay

across

a region crowded with steep rocky hills till it reached the Tiber

Valley,

and Rome itself, some 23 miles distant. Much of the region was heavily

wooded with pines and chestnut trees, and many of the hills bore the

now

familiar terraces on which olive orchards and vineyards were planted.

The 337th and 338th

Infantry

Regiments had relieved elements of the 3rd

American

Division {actually

called

3rd 'Marne' Division}, and the Division

Artillery was brought up to take positions in support of the

infantry. At 1 o'clock in the afternoon of May 31st the attack began.

The

1st Battalion of the 337th on the right and the 3rd on the

left

advanced on either side of Lariano, by-passing the town. The 2nd

Battalion

sent a reinforced company into Lariano to wipe out the rear guard

there,

which it accomplished only after a bitter, prolonged fight.

The 3rd Battalion was now moving along a front

slightly less than a mile wide, down the slopes of a ridge thickly

covered

with rows of vineyards. The advance went slowly, but one company in the

early evening had reached the opposite slope and consolidated positions

there.

On June 1st the 338th Infantry,

advancing

north of Lariano, overcame stubborn resistance in the morning but late

in the day the enemy resistance failed, and the signs of withdrawal

were

unmistakable.

That midnight the regiment was relieved by the 351st

Infantry Regiment of the 88th

Division. but when it was seen that the enemy retreat was

about

to turn into a rout the 338th was recommitted immediately to

pursue the badly beaten remnants of the Goering

Division. On the night of June 2nd the battalion entered San

Cesareo and cut Highway 6, killing a large number of Germans who were

trying

to escape along the road. At this point the regiment passed to Division

reserve except for the 3rd Battalion which was attached to the 339th

Infantry to become the reserve battalion for that regiment.

The 339th Infantry, passing through

Giulianello on June 1st, attacked through thickly wooded hills

to

seize Castel D'Ariano, the highest point of the Maschio D'Ariano Hill

Mass.

Progress was steady and quick for several miles, the only resistance

fire

from snipers and an occasional self-propelled gun. But the next day, as

the regiment veered to the northwest, it met resistance from mortars

and

artillery on Monte Fiore, southwest of Rocca Priora. But this

resistance

was reduced in short order, and on June 3rd the regiment seized 2 more

hills, Monte Salamone and Monte San Sebastiano.

Just south of Monte Compatri the 85th

Reconnaissance

Troop ran into a heavy fire fight the night of June 3rd, in which they

killed 40 of the enemy and took 65 prisoners. The next day

elements

of the Troop cleared Frascati of snipers. The 339th Infantry

occupied the town somewhat later, and went on to advance to within 3

miles

of Rome when it halted for the night.

The 337th Infantry continued to

meet

heavy resistance. Through the thickly wooded draws motorized patrols

and

roving snipers harassed the troops, and several times wedges were

driven

into the exposed right flank of the 1st Battalion. At one time the

infiltrating

enemy completely surrounded the 1st Battalion CP, and it was necessary

to round up every available man to scout out and kill the enemy. Tank

destroyers

were meanwhile brought up to aid the 3rd Battalion, tanks

were

aiding the 1st, and now hill after hill fell into our hands.

In this sector resistance was still stiff. The

enemy did not want to give in. But by nightfall of June 2nd the troops

had pushed through to seize Monte Ceraso, and the 2nd Battalion had

reached

a point only 1200 yards south of Highway 6. By this time they

were

more than 2 miles in advance of the rest of the line.

On June 3rd new orders changed the direction of the

regiment's

advance from north to northwest. By now contact was lost with the

enemy,

and the 1st and 3rd Battalions, in approach march formations, moved

west

on parallel roads. After an interval the 2nd passed through the 1stto

capture

Monte Compatri without much trouble. Some light resistance was met

before

Monte Porzio Catone was taken, but this was soon wiped out.

Before

us now lay the Tiber, and in the early morning the domes of the

churches

of Rome could be clearly seen, the

first sight of the beautiful prize of weeks of hard fighting. In the

warm

sunlight of May the city seemed to be waiting for the troops to enter

it.

One company of the 3rd Battalion of the 337th,

motorized and reinforced as a task force, supported by tanks, tank

destroyers.

engineers and artillery, was now ordered to advance along Highway 6

into

Rome and to seize and protect 2 bridges across the Tiber west of Rome.

The I and R Platoon, preceding the advance, had reached

the

suburbs of Rome by half-past eight the morning of June 4th, the

first troops of the Division to reach that city.

{ There is much discussion as to which American unit can claim to be

the

first to enter Rome. I agree with accounts that say the Recon

Troop

of the 88th Division was first. The noted time may be a

clue.}

At the city limits the task force was held up

by an armored unit engaged in wiping out an enemy strongpoint along the

road, and while here orders were received again changing the mission of

the regiment. The 337th was ordered to turn south- -west to take up a

defensive

position' astride Highway 7 about 4 miles out of Rome, and to prevent

any

further enemy withdrawal by that route. Pressing ahead through the

traffic

congestion of VI Corp troops

speeding

along the highway into Rome the regiment cut the highway. This move was

in large part responsible for the capture of 743 prisoners taken by the

Division in the 24-hour period from noon to noon 4th - 5th June. In

marching

from Frascati to Rome the 3rd Battalion, 338th Infantry accounted for

300prisoners.

A task force composed of the 2nd Battalion of.

the 338th Infantry, reinforced by tanks, tank destroyers,

and

engineers, was sent into Rome on June 4th to secure 3 ridges across the

Tiber in that city. Preceded by the regimental I and R Platoon, this

force

entered Rome in the middle of the afternoon, and by nightfall had

reached

their objectives, which, however, were already guarded by a Special

Service

Force whom they later relieved.

| GO

TO Map

4 – The Drive Beyond Rome - June 4 –

10,

1944 |

June 5th saw the advance of the Division through

Rome.

Entry into a conquered capitol must always be one of the greatest

experiences

a soldier may know. Everywhere the people ran out into the streets to

hug

and kiss and shake hands with the marching soldiers, shouting and

cheering.

They ran beside the jeeps and trucks, chattering and laughing

unrestrainedly,

throwing flowers, waving their hands, and some of them pathetically

saluting

in the Fascist manner. It was a spontaneous, happy welcome.

On June 5th the 339th Infantry

passed

through the city and along Highway 2 to a bivouac area

northwest

of Rome. The 338th and 337th Regiments followed,

and the pursuit was continued.

Following along Highway

2 to the northwest towards Viterbo and the Lago di

Bracciano

there were more and more of the signs of the routed Germans - burnt out

and abandoned wreckage everywhere - though here it appeared that the

enemy

had had no time to wreck his own equipment. The Germans had fled in

everything

they could lay their hands on, ambulance, trucks, Italian omnibuses,

motorcycles,

and bicycles.

North of Rome Highway 2 wound through

gentle

rolling country, rich pasture land, well tended olive vineyards, and a

few patches of woods. At some places a hill or a bluff offered the

enemy

the opportunity to set up a number of delaying positions, and snipers

were

still found in the haystacks. But more often than not contact was lost

with the enemy these first days above Rome. The Germans were now

retreating

towards the Arno as fast as they could travel.

The 339th Infantry had pursued the

enemy beyond Olgiata when it passed to reserve. The other 2 regiments

took up the chase, passing through the 339th.

These

were organized as combat teams, each with a company of tanks, a company

of tank destroyers and a platoon of the 85th Reconnaissance

Troop attached. On June 7th the Howze Task

Forcewas

attached to the Division, and this fast armored unit, with the 1st

Battalion

of the 337th Infantry attached, drove ahead to give the

enemy

no chance to pause.

These forces met small groups left behind to

man

a few self-propelled guns, some groups in armored cars and firing

automatic

weapons made harassing raids, and here and there a machine gun made a

short

stand. Near Monterosi the approaches to the village were mined, but

nothing

was more indicative of the enemy's haste and his inability to organize

any substantial delaying action than his failure to lay extensive

minefields.

Each day the prisoners were taken in

droves,

the confused, isolated remnants of the rout. Among these were members

of

a cooks and bakers school the enemy had seen fit to give rifles and

orders

to delay and hinder our advance. In the great mixture of forces left

behind

in the rout were parts of the 20th

German Air Force Division and the 4th

Parachute Division, the latter to be our first opponent on

the Gothic

Line. {

20th German Air Force Division was one of 2 infantry divisions made up

of air force personel. By 1943, the Luftwaffe was ineffective and

personel were transferred into twenty-one divisions. The 19th and

20th LFD served in Italy. Officially known as Luftwaffe Field

Division.}

But now the Divisions part in driving the enemy

north

was coming to a pause. On June 10th the Division was relieved from the

line some 46 miles beyond Rome. Since April 10th it had been in action

60 out of 62 days. Since May 11th it had advanced 135 miles,

breaking

the Gustav Line, opening the road

to

the Anzio Beachhead, and playing an important part in the capture of

Rome.

It had virtually destroyed the German 94th

Division

and cut up much of the 29th and

the Goering

Panzer Grenadier Divisions. From these units and all the

other

scrambled organizations of the enemy it had taken 2461 prisoners.

Now had come the time for a rest.

BETWEEN ATTACKS

Shortly

after relief from the line the units of the Division began moving to

bivouac

area a few miles south of Rome, on the grounds of the Castel Porziano,

a large hunting estate belonging to the King of Italy. Here for a

period the troops rested before resuming training, and here they

obtained

their first passes permitting them to visit Rome, and. to enjoy the

city

they had helped to capture.

On June 18th, in recognition of distinguished service

as

Commanding General of the Division from May 11th to June 10th, General

George C. Marshall, Chief of Staff, United States Army, presented the

Distinguished

Service Medal to Major. General John B. Coulter.

The

Division remained in the Castle Grounds until July 10th, continuing

training,

and giving special instruction to the replacements who were being

received

at this time. Then began the movement to the vicinity of

Rocccastrada,

about 150 miles to the north, where further training was conducted

preparatory

to whatever new mission might be assigned the Division.

On July 17th the 339th Regimental Combat

Team

together with the 85th Reconnaissance Troop was ordered to

move

to the vicinity of Volterra where it was placed in the Fifth Army

Reserve

prepared to resist any counterattacks the enemy might make along the

boundary

between the American Fifth and British Eighth Armies. The

commitment

of the Division, however, waited upon the accomplishments of. other

units

of the Allied Armies and the maturing of.various plans. At one time it

appeared that the Division might take part in the attack on Leghorn and

the remaining elements of the Division were accordingly moved on July

18th

to the vicinity of Rosignano Marittimo, a few miles in from the

Ligurian

Coast below Leghorn. But it soon became apparent, after the capture of

Leghorn, that the Division would take part in the operations farther

east

along the Arno River. On July 28th the Division was ordered to

assemble

in an area between Volterra and San Gimignano, the famous medieval city

which once had 73 towers. In this region. the troops continued their

training

in river crossing and mountain warfare. The 339th Combat{Team}now

returned to Division Control.

At first the Division prepared to take part in an

offensive

operation, that of crossing the Arno and attacking to the norht.

But these plans were changed and between August 15th and 17th the

division

took over the defense of the Arno on a front extending along the south

banks of the river from near Bellosguardo on the east to Capanne on the

west, a distance of about 24 miles. Over this extensive front the

Division set up strong points and outposts. After the 19th of the

month the Division's sector was increased still farther. Since

all

3 regiments were already stretched out along the line, the 85th

Reconnaissance

Troop and the 310th Engineer Battalion were assigned sectors which they

held, functioning as infantry. The division front now extended

2000

yards farther to the east.

The chief enemy forces opposing us at this time were

elements

of the 26th Panzer Division, the 3rd

Panzer Grenadier Division, and the 362nd

Infantry Division. The north bank of the Arno rose

quickly

into hills, and holding these the enemy generally commanded good

observation

of the country to the south. He also continued to maintain a few

strong points on the south side of the river, notably at La Lisca,

Fornaci

and Tinaja. Since our supply routes were generally under

oservation,

most of our traffic during the day the enemy shelled the roads, but

otherwise

his firing was chiefly of a harassing nature. On most days fewer

than 400 rounds fell in the division sector, though that many fell in

one

concentration at the time the 310th Engineers were moving into their

sector.

As it happened, there were no casualties on this occasion.

Our units regularly sent patrols to the banks of the

river,

and some patrols and raiding parties were sent to feel out the enemy

positions

on the opposite bank and to take prisoners. On his part the enemy

conducted even more aggressive patroling since it was his rather than

our

forces expecting to be attacked. From German prisoners taken at

this

time it was learned, and correctly, that the enemy intended to withdraw

in the even of a full-scale attack, but that otherwise he would merely

resist our patroling and infiltration. In order to determine if

and

when we would attack he sent patrols and raiding parties into our area,

mostly at night, and these groups operated very boldly. Stiff

firefights

sometimes developed, but as a whole the period passed quietly.

On August 26th the Division was relieved from the line,

and moved south to assembly areas between Montespertoli and Certaldo,

on

the slopes of the ridge separating the Elsa and Pesa River

valleys.

After 2 days rest the troops resumed training in the well-cultivated

and

beautiful country of mid-Tuscany. While here the expectation of

big

things to come began to grow. The day was not far off when the

Allied

attack on the Gothic Line would get under way, the system of German

defenses

protecting the great ridges of the Appennines and the descent into the

Po Valley. Accordingly the training was pointed more and more

towards

the problesm of mountain warfare.

Occasionally the enemy sent over a few planes to bomb

and

strafe the roads and installations in nuisance raids. Beaufighters were

up to cut him off, but on many nights a solitary German plane, known to

many as "Bed-check Charlie" came over in the bright moonlight, dropping

his flares and bombs and scooting back. Now and in the months to

come this was the usual effort of the German Air Force, accomplishing

not

much more than letting us know he still had some aircraft in Italy.

THE GOTHIC LINE

{September

1944}

After

the Germans lost Rome they were driven farther and farther north along

the entire breadth of Italy. Withdrawing as fast as possible to the

next

natural barrier, the Arno, they had fought delaying actions in the

hills

to the south of the river, but their next main line of defense was the

Gothic

Line, extending roughly from north of Pisa to Rimini. For

about

a year the Todt Organization had

been

constructing a line of defenses over the great mountains of the

northern

Appennines. After the collapse in southern Italy the construction of

these

defenses had been greatly speeded up, and they had now become a

formidable

defense system.

The mountains themselves were difficult obstacles to an

attacking force. Rising steeply to a great ridge whose peaks varied

from

3000 to 5000 feet high, crossed by few roads, these masses offered

difficulty

even in scaling. Beyond the first ridge 20 miles farther north rose

another

high ridge before the descent into the Po Valley began. It was the

first

ridge, the watershed, that the enemy was defending.

The American Fifth and British Eighth Armies in the

first

weeks of September launched a coordinated attack against this line.

Fifth

Army was to attack the western half, and II

Corps

was making the main effort of Army on the right flank. The 85th

Division, when it joined in the attack, was to make the main effort for

Corps on the Corps' right flank. The problem that faced the Division

initially

was to cross the mountains, breaking through that part of the Gothic

Line

defending Il Giogo Pass through which wound the single first-class road

to the north in the Division sector.

As the Division moved up through Florence in the second

week of September the mountains facing it appeared a solid wall. After

the ascent began the growth thinned out. At the top there was little

but

great splintered rocky masses and steep cliffs.

Here and there along the lower slopes a cart road wound

to a solitary stone farmhouse, beyond these mule and goat trails

climbed

a short distance into the scrub and vanished, and then there was

nothing

but ragged rock. The highway, which passed through Il

Giogo (Pass), was bordered by stands of pine and hemlock,

but

most of these before and during the attack were reduced to stumps and

torn

branches by the terrific concentrations of artillery fire.

Lacking

road, mules and men brought up supplies on their backs. Approximately

1000

mules supported the operations.

The fall rains had begun in the first days of

September,

but these had let up before the attack. The weather was now often clear

and bright, though in the evening and early morning, mist settled in

the

ravines and draws. The autumn chill had begun, but there was no frost.

At the beginning of the attack the 1st

Battalion

of the 12th Parachute Regiment

of the 4th

Parachute Division composed the chief forces opposing the

Division.

Later, elements of the 3rd Battalion were thrown in when it

was evident that a main effort was being made here.

Altuzzo,

immediately

to the right of Il Giogo Pass,

dominated

the road passing over the mountains to Firenzuola, and from his

positions

on this mountain and on Monticelli, in the 91st

Division sector on the left, the enemy denied our forces the

use of the road. East of Altuzzo the next mountain, Verruca, was also

strongly

fortified, and from this the enemy not merely protected the ridge but

was

also able to fire upon troops attacking Altuzzo.

Approaching Altuzzo from a low ridge, the ground sloped

steeply to a narrow stream. Beyond its steep banks a gradual slope

fanned

out for a few acres in pastureland and cultivated fields. This slope

was

inclosed on 3 sides by a fringe of woods and brambles until the slopes

and ravines of the mountain itself were reached. Troops moving up from

the stream into the fields along the bordering woods were exposed to

view

from 2 and sometimes 3 sides of the arms of Altuzzo. The ridge leading

to the southern crest of the mountain, Hill

926,

included 3 hills 578, 624 and 782. The formation of Verruca was

similar,

the advance leading up steep ascents and ravines. The approach followed

by the forces attacking the summit, Hill 930,

led along the ridge including Hills 591, 732, and 724.

The enemy bunkers were on the forward slopes. Dug 20 to

30 feet into the ground and rock, covered with great piles of enormous

logs and boulders, with the fire slits opening through rocks of fallen

trees, these bunkers were vulnerable to artillery only if hit directly.

The infantry would be obliged to clear them individually. Machine gun

nests

and connecting trenches were protected by logs and slabs of rock.

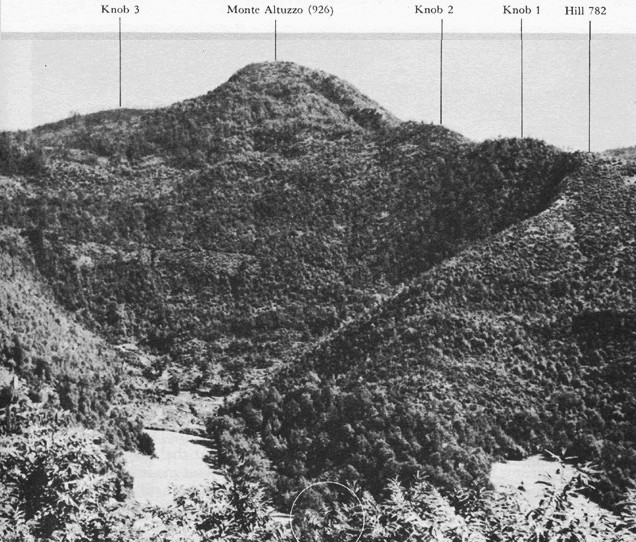

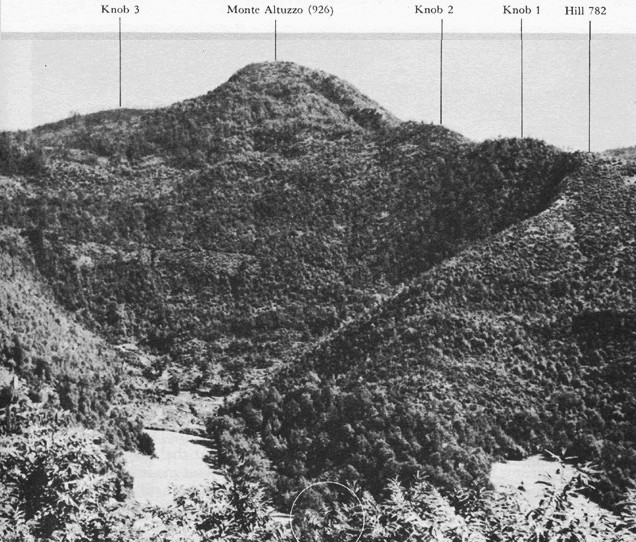

A view of the

approach to Monte Altuzzo. The 338 Regiment started from

the gulley in center of this photo and advanced

along the ridge do the left.

A view of the

approach to Monte Altuzzo. The 338 Regiment started from

the gulley in center of this photo and advanced

along the ridge do the left.

|

GO

TO the Biography of Pfc

Kemit Fisher to read details on the final assault of the peak.

|

| GO

TO Map

5 – The Attack on the GOTHIC Line -

September 13-17,

1944 |

The

Division attacked at 6 o'clock on the morning of September 13th.

To begin with, 2 regiments were on the line, each with 2 battalions

abreast.

On the left the 338th Infantry attacked towards Altuzzo, and

the 339th, on the right towards Verruca. During the early

hours

of the morning a tremendous artillery barrage had been laid upon the

enemy

positions by the Division Artillery and the supporting II Corps

artillery

units. The barrage was not concentrated in such a short period of time

as that proceeding the Minturno push, but the total number of rounds

fired

was even greater. The great 240's, now and during the entire attack,

were

an especially important factor in the smashing and gradual

demoralization

of the enemy. The air force also sent over planes to bomb and strafe

the

roads and the supply installations in the rear as well as the

emplacements

on the crests.

The 1st Battalion, 338th Infantry

attacked on the left of the regimental sector in a column of companies.

The 2nd, on the right, attacked with 2 companies abreast.

All

were immediately met by intense mortar barrages and small arms fire

that

increased in intensity as the day wore on. The 1st Battalion

moved from south of La Rocca and in the midst of this storm of fire

attacked

towards Hill 926. By dark, however, it had made little substantial

progress.

The 2nd Battalion met no better fortune.

The 339th Infantry, with the 1st

Battalion on the left and the 2nd on the right, advanced

towards

Verruca, moving up Hill 617 and the Poggio Rotto Ridge. Their advance

was

quickly blocked by severe artillery concentrations and grazing machine

gun fire. This was so intense that the troops had no opportunity to

improve

the positions they had won initially. Tank destroyers of the 805th

Tank Destroyer Battalion began firing on the 3 fortified

house

on Hill 591 that blocked the way to Verruca, and during the day and

night

the resistance here was gradually beaten down. One company of the 2nd

Battalion succeeded in coming within 150 yards of the Verruca crest,

but

as yet no permanent progress was assured.

The first day's attack, in short, had made little

headway.

Though the difficulties of the attack were becoming clearer, there had

been no expectation that this would be an easy battle. What was called

for was a constant hammering. Accordingly, while the troops dug in, the

artillery kept up intermittent fire throughout the night, and in the

early

morning let go with another tremendous barrage before the infantry

jumped

off again.

This time the 1st Battalion of

the 338th made somewhat better progress. Company B,

spearheading

the attack, reached a point within 75 yards of one of the crest of

Altuzzo.

Company E of the 2nd Battalion tied in with

the

left of B Company to keep abreast of the advance. But the gains

they made were not to be easily held.

B Company, advancing over rocky, exposed

slopes,

came to a point where it had little cover and where it soon found

itself

fired upon from 3 sides by machine guns. Even while it attempted to

prepare

itself for defense the enemy began counterattacking, in a repetition of

the same, long-tried German tactics, and the Germans were repulsed each

time. For its action on Altuzzo, B Company received a

Presidential

{Unit}

Citation.

For

conspicuous gallantry in the attack on Altuzzo on September 14th,

Staff

Sergeant George D. Keathley, B Company, 338th Infantry,